It's crunch time for politicians in Maharashtra with drought and agrarian distress looming over the high-voltage drama of elections.

The initial, high-pitched drama over selection of candidates and last minute defections played out mostly in television studios has given way to starker realities on the ground.

Drought and rural distress are ravaging the state this election summer, with little or no change from the past.

From Vidarbha and Marathwada, which voted in the first two phases on April 11 and April 18, to western Maharashtra, Konkan, Mumbai and northern Maharashtra, where polling would be held on April 23 and April 29, the voters’ disenchantment with politicians is evident.

“Kay Farak Padnar Aahe,” (What difference will it make) and “Sagle Saarkhe,” (All [are] the same), is the common refrain from across the state’s six regions.

The scarcity of water is particularly critical in Marathwada and western parts of Vidarbha, Jaidev Gaikwad, a senior Ambedkarite leader and state chief of NCP’s social justice cell, said.

Gaikwad, who campaigned extensively in these regions during the initial phase and was now touring the drought-prone eastern parts of western Maharashtra, said rural distress was a key issue.

The situation continues to be grim in Latur district, which, along with Osmanabad, has been the epicentre of the annual droughts in Marathwada. In 2016, a special ‘Jaldoot’ train made over 100 trips to ferry drinking water from Sangli district covering a distance of 343 kilometres to quench the thirst of residents of Latur city and adjoining rural areas.

This year, there is no such hope with the eastern parts of Sangli in western Maharashtra also battling severe drought conditions.

Besides Marathwada, stories of water scarcity, human and cattle migration are emerging from Sangli and Satara districts, key regions of the sugar-belt in the state.

A senior BJP functionary from the sugar belt of western Maharashtra said on the condition of anonymity that though the Devendra Fadnavis government had done a commendable job, the water situation was turning critical.

“This drought and accompanying agrarian crisis may cost us heavily in rural areas,” he admitted.

The BJP functionary was referring to Fadnavis’ much-publicised ‘Jalyukta Shivar Abhiyan,’ launched in 2014 to conserve water, especially in the drought-prone areas of the state. The scheme was touted as a “grand success” with officials claiming the increasing groundwater levels had substantially reduced the dependence on water tankers in many parts.

The Fadnavis government claimed to have implemented ‘Jalyukta Shivar’ in 16,522 villages by spending more than Rs 7,500 crore.

But at the fag end of its term, drought, water shortages and prospects of lower crop produce loom over more than half the state.

The government had declared 151 tehsils as drought-hit by the end of previous year.

Early this year, it added 931 villages from eight districts in Marathwada, western and northern Maharashtra to the list.

“We launched relief measures as early as December-January in all revenue villages with average rainfall less than 75 per cent or crop produce less than 50 per cent of the estimate,” Relief and Rehabilitation Minister Chandrakant Patil said.

The situation has worsened ever since. As of now 26 districts were officially declared drought-hit. Latur city was being supplied water only once in a fortnight.

The price of drinking water had shot up from Rs 700 to more than Rs 1,000 for a 5,000-litre tanker, while cattle was being pushed into government-run camps by the thousands in the affected districts, the Swabhimani Shetkari Sanghatana said.

Yet, all the political parties in Maharashtra – except perhaps the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena’s Raj Thackeray, who alluded to the worsening drought in Marathwada in some of his recent public speeches – had chosen to ignore the crisis in their manifestos or election campaigns.

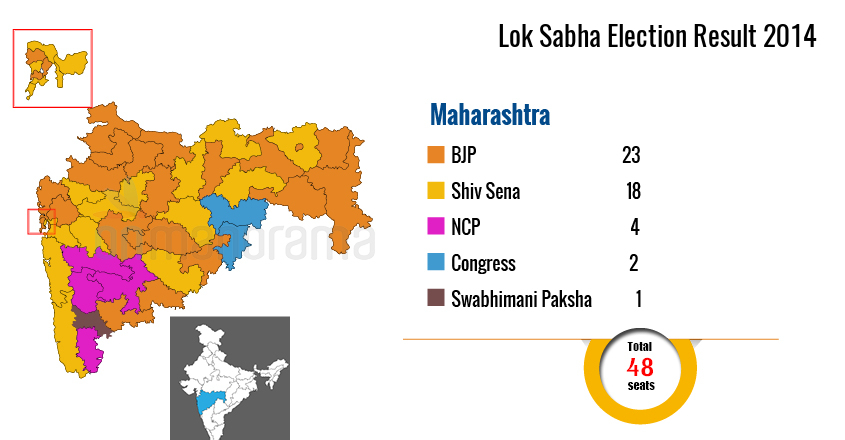

In fact, Chandrakant Patil of the BJP was confident the saffron combine would fare very well in Marathwada, Vidarbha and even western Maharashtra, considered a stronghold of the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP).

Patil was spending much of his time focussing on wresting Sharad Pawar’s pocket borough of Baramati, now represented by his daughter, Supriya Sule, and neighbouring Madha, his former constituency spread across the drought-hit parts of Satara and Solapur districts.

The lay man's ongoing battle with drought did not find a space in the mainstream media coverage initially, though the print, more than television, began catching up midway through the elections.

“Media should be showing the true picture from the ground, but we don’t see that happening,” Jaidev Gaikwad said.

But he could sense an “undercurrent” of “mass discontent” both against the Narendra Modi government at the Centre and the Fadnavis government.

Gaikwad claimed the NCP chief’s meetings in rural parts as well as urban centres like Solapur and Kolhapur were drawing huge crowds. “The NCP-Congress alliance will do well in rural Maharashtra. The urban areas too will see a tough battle between us and the rival BJP-Sena,” he said.

But Chandrakant Patil, who hails from western Maharashtra and is in charge of the region, remains unfazed.

He was confident the BJP’s strategy of engineering defections from the rival Congress-NCP camps will yield favourable results in the sugar belt.

“We will achieve ‘Shatpratishat’ (total) success,” he said.

Ironically, the current drought situation appears a throwback to the early days after India’s Independence, described very powerfully by one of Marathi literature’s doyens, Vyankatesh Madgulkar, in his novella about an obscure village located in present-day Sangli district.

First published in 1955, ‘Bangarwadi’ narrated the woes triggered by a drought in what was once part of the princely state of Aundh in Bombay Presidency and now happens to be located in the drought-prone Atapdi taluka in the heart of Maharashtra’s prosperous sugar bowl.

The story of how this village of simple shepherds – where abject poverty is the order of the day – falls apart in the face of a looming drought, forcing its residents to migrate, was hailed by Economic and Political Weekly as “perhaps the most important book written by an Indian about India to appear in English since Nehru’s ‘Discovery of India’,” when its English translation titled ‘The Village had no Walls’ was published in 1958.

The original work, in its 25th edition now, remains a milestone in Marathi literature and was adopted for the big screen by Amol Palekar in 1999, wooing audiences and critics alike.

“I named it Bangarwadi. The real name is Lengrewadi,” Madgulkar wrote while introducing a new generation of readers to a special edition published that year.

Lengrewadi, with its 1,525 residents according to the 2011 census, continues to exist in the dark shadows of the drought-prone region.

And like in the early fifties, most of its residents have already left the village this year.

A recent survey conducted by the Sangli district administration revealed more than 16,000 registered voters from Atpadi and neighbouring Jat taluka had migrated due to the looming drought.

They were supposed to vote on April 23.

This is proof of how little has changed for the ordinary Maharashtrian folks, elections notwithstanding.