The third place finish in Pathanamthitta and Thrissur Lok Sabha constituencies in Kerala will not rankle the state unit of the BJP the way the near one-lakh drubbing it suffered in Thiruvananthapuram would.

In Pathanamthitta and Thrissur the party can at least take heart in the fact that the BJP's vote share had gone up stupendously. (K Surendran of BJP had taken it to 28.94 per cent from a modest 16.29 per cent in 2014 LS polls. Suresh Gopi's feat in Thrissur was even more commendable. From a mere 11 per cent in 2014, he amassed 28.19 per cent of the votes.)

However, in Thiruvananthapuram, where the BJP had already emerged as a bigger force than even the Left, the party could not even sustain its 2014 level. From 32.45 per cent it fell to 31.25 per cent.

Paper tiger

During the campaign, it looked as if the BJP had everything going for it in Thiruvananthapuram. Not to leave anything to chance, especially because the BJP was prone to internal turf wars, the RSS had taken full control of the campaign. Add to it the money power, and the Sangh Parivar put in place by far the most efficient campaign machinery in the constituency. The target was 4 lakh votes, and it did not seem unattainable.

The campaign was so driven that even in coastal areas where there is a thick concentration of Christian and Muslim families, children were seen playing with Modi masks. These were areas that the party had largely ignored in 2014.

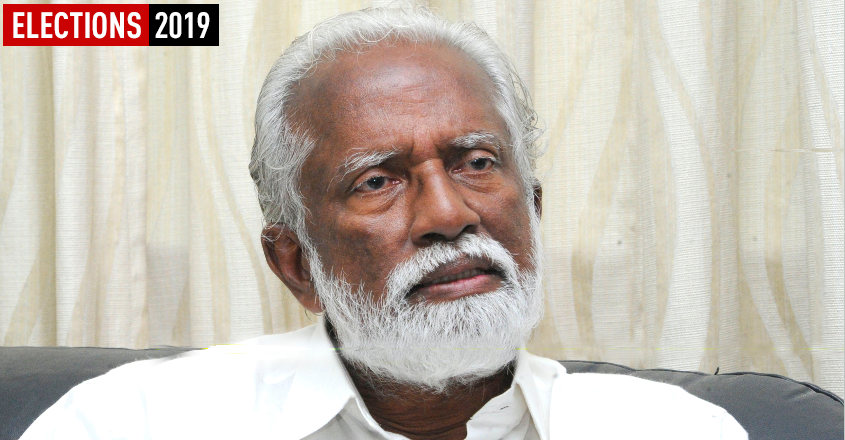

To top it all, there was Kummanam Rajasekharan. He was not just widely accepted within the organisation but was also revered as a paragon of virtue even by those outside the Sangh Parivar. Yet, Kummanam lost badly, embarrassingly. As it turned out, it was Shashi Tharoor who crossed the RSS target of 4 lakh votes. Kummanam's tally was nearly one lakh short.

Fury of the coast

Minority consolidation is the first excuse the BJP leaders shout in defense. In hindsight, top leaders Onmanorama talked to admit, the party could have easily foreseen this and promptly reassured the minorities. Here, there was strategic confusion. “We should have reached out to religious leaders in a big way rather than in the half-hearted manner we had gone about the task,” a senior BJP leader said. “We feared it would dilute the hard Hindutva stand the party was taking across the country and therefore was in two minds,” he added.

In fact, the BJP campaign had penetrated deep enough. The party cadres visited Christian and Muslim houses in coastal areas three to four times, trying to assuage their concerns about a Modi government. However, the various church denominations remained aloof. “The Congress was able to give the impression that Rahul Gandhi would come to power,” the BJP leader said. The BJP vote share in Kovalam, which was historically low, dropped by nearly one per cent this time.

Where did the Hindu votes go?

The other alibi that the BJP trots out is that it had lost the NSS and SNDP, essentially Hindu, votes. To say that the BJP has lost NSS and SNDP votes is to assume that they had a near monopoly of the community votes earlier. This is not the case.

Historically, even when the BJP was not a strong presence, the party had received a fair slice of the Hindu votes in the constituency. But the votes were distributed among all the three formations, with a clear preference for the UDF. But in 2014, there was a decisive shift of Hindu votes to the BJP. The voting trend this time shows that the BJP has more or less held on to its 2014 vote share; there was only a marginal drop from 32.45 percent to 31.25 per cent.

Nair's anger and Modi's phone call

So the question to be asked is not why Hindu votes were lost but why was the BJP unable to widen the Hindu support base it had created in 2014. One explanation trotted out is that the party was not able to keep NSS general secretary Sukumaran Nair in good humour.

“Sukumaran Nair was not pleased that Kummanam made only a fleeting visit to his place. We were told that he was upset that Kummanam had not shown him enough respect,” a senior leader who was in charge of reaching out to community leaders said.

“When we were exploring ways to mollify him, we were told that Sukumaran Nair would be satisfied only if the prime minister called on him at the NSS headquarters at Perunna. This was a tall ask but we managed to get Modiji to talk to Sukumaran Nair when he came on a campaign visit. They talked for some time and Modiji asked for his support. Even after this, Sukumaran Nair did not send instructions to 'karayogams'. He did not even ask his community members to at least vote according to their conscience. He just kept silent,” the BJP leader said.

Pure soul image

But Nair's indifference could have been made up, BJP insiders say, had Kummanam shed his Buddha-like image and been more caustic. “Never once did he take the name of Ayyappa Swami. He played by the book. See how Suresh Gopi reaped rich dividends by uttering Ayyappa's name during the campaign,” a leader said.

In fact, the non-combative style of Kummanam had come in for some severe criticism during the campaign. “If the strategy was to present Kummanam as a virtuous pure soul, as our posters had suggested, the party should have shown Shashi Tharoor in a bad light. This was not done. Only when the other person is seen as really bad will your candidate's glow look more divine,” a top BJP idealogue said. Amit Shah, too, had given the party licence to adopt in-your-face tactics to win.

Emboldened, a charged-up section within the party wanted to revive the controversy surrounding the death of Sunanda Pushkar. In 2014, O Rajagopal had brought the man who was instrumental in taking the death of Sunanda to court, Subramanian Swamy himself, to talk to the voters in Thiruvananthapuram. This time, Kummanam was not open to the idea.

Old men's curse

Kummanam's fair play might or might not have hurt him but there is now a consensus within the party that the continued apathy towards old warhorses like P P Mukundan and Raman Pillai had cost the party dear. “Raman Pillai was made the campaign committee vice-chairman but was not provided even a chair to sit, leave alone an office. After attempting three times to get a room, he left the campaign scene,” a BJP leader said.

Mukundan, who was already sulking when Kummanam was announced as candidate, is said to command huge respect of the BJP cadres across the state. “I think we should begin our fight back in the state by giving these veterans party posts befitting their stature,” the leader said.