Meet Cheruvayal Raman, the guardian of native seeds from Wayanad

Mail This Article

Dew drops on young paddy stalks glisten in the morning sun at Cheruvayal Raman's 6-acre-farm in Kammana, Wayanad. It is barely day-break but Raman is already there tending to a patch of vegetables. “This spinach looks good. Wait for two more days for it to mature and it can make a good upperi,” he says. He walks barefoot, his legs sinking into the moist soil with each stride.

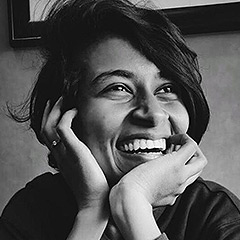

Though rugged and sun-beaten, Raman looks much younger than his 73 years. He belongs to the Kurichiya tribe, the traditional paddy cultivators of Wayanad. This year, the Union government honoured him with the Padma Shri, the fourth-highest civilian award, for his efforts to conserve indigenous rice varieties of Wayanad. “I have preserved around 60 varieties of paddy seeds. I have set aside one cent each for the 60 varieties,” he says.

These seeds have a shelf life of about eight months after which their quality would start to deteriorate. “That is why it is important to keep growing them every season,” Raman says.

Every season, Raman gives his fellow farmers 500g of seeds from each of these indigenous varieties. “Once these farmers harvest their crop, they return the same quantity of seeds from their farm. I don't sell my seeds. I do this to make its cultivation popular,” he says.

There was a time when Wayanad produced more than 100 rice varieties. “We lost most of them to new-age farming practices. The introduction of hybrid seeds broke the way we viewed agriculture. These high-yielding variants needed chemical fertilisers and pesticides for their growth. But that altered the soil quality and killed the small animals that lived on the farms,” he rues.

Conservation, all the way

Raman took to farming at a young age. It was his maternal uncle who inspired him to stick to native seed varieties. “In the early 1970s, many people from the Kurichiya tribe moved to hybrid seed cultivation. But my uncle noticed the drawbacks of the new seeds," he says.

Unlike the local varients with long shoots, the hybrid ones were shorter. "This meant we couldn't use it to thatch our huts," he says. His uncle also noticed the imbalance in the local ecosystem due to the use of chemicals. "So from 1978, we returned to our traditional agricultural ways,” he recollects.

After his uncle died in 1989, Raman took up independent farming. “He left me with six indigenous varieties of seeds. I took it upon myself to collect more of them. I worked for almost three decades and many trips across the state to gather them.”

Seed goodness

Raman's selection of seeds has varied maturing periods. Varieties such as veliyan, chettuvelliyan, and mannu velliyan have the longest yielding time of 200 days. Thondi, chenthondi, kandi chennellu, chennellu, and valveliyan require 150 days to mature, while onaattan and kalladiaryan take 120 days. The shortest yielding period is 90 days for seeds like thonnooram punja, thonnooram thondi, and njjavara.

It takes a minimum of seven days to prepare the seeds once they are harvested. “We select the best seeds of the season. It is then husked and dried for seven days. These seeds are then stored in baskets and jute bags till it is sowed in the next season," he says.

Future farming

Though he has been working in the fields for over 60 years, Raman feels that the future of agriculture and his seeds is bleak in the state. The hesitation of youngsters to take it up and the poor returns from farming add to his worry. “Agriculture does not give assured returns. For agriculture to thrive, I suggest the government give remuneration to the farmers in proportion to their farmland. The government should also give other medical allowances, education quotas, and family insurance. This is the only way it would survive,” he says.

(April 26 is observed as the international seeds day to recognise the importance of seeds.)