Column | A Malayali saint, Sanskrit school and socially inclusive education

Mail This Article

Many children growing up in 21st century India have little idea about the role played by Christian missionaries both in the country’s independence struggle and in educating the masses at a time when quality education seemed like a distant dream for a poor person.

In the beginning of the 19th century Kerala had highly restrictive practices when it came to education. At that time, children learned reading, writing and arithmetic at a traditional village school called an Ezhuthu Kalari. Given the prevalent complex caste structures in the state, these schools were usually accessible only to high caste Hindu children, although there are documented cases of Syriac Christians also studying in them.

“Though Malayalam was the medium for communication, most of the literature was in Sanskrit,” Joseph Varghese Kureethara, wrote in a paper for The International Catholic Journal of Education. “As a classical language, Sanskrit kept its elitism and hence was away from the reach of the common man.”

Mannanam Sanskrit School

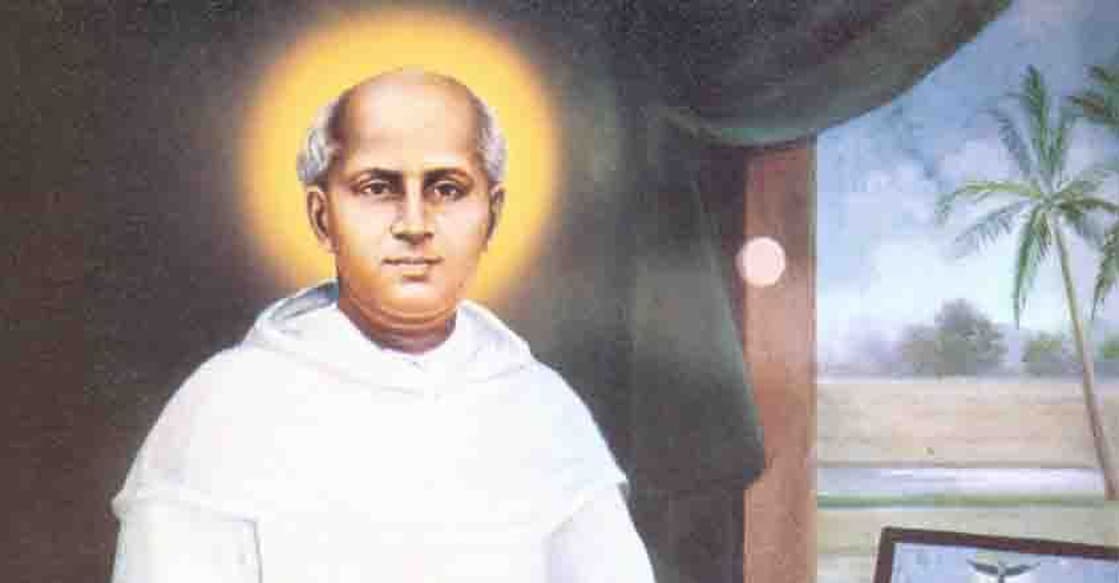

Mannanam, a village in the Kottayam district, was at the vanguard of a movement to bring education to the weakest sections of society. The story began in 1831 when Kuriakose Elias Chavara, a 26-year old priest, co-founded a monastery in the town with two fellow priests.

Hailing from the Syriac Christian community, Chavara (who was also educated in an Ezhuthu Kalari) was moved by the plight of the members of the lower castes. Converting to Christianity did not seem to save them from discrimination, despite the concept of caste not existing in the religion.

In 1846, Chavara took the bold decision to open a Sanskrit school in Mannanam. The school was open to Catholics as well non-Catholics, and children from the lowest castes were welcomed to join. He preferred Sanskrit over English for a number of reasons. At that time, the Catholic Church did not encourage people in Kerala to learn English, as the language was seen as a medium to convert people into Protestantism.

“The status that Sanskrit had among the people in the upper layer of the then society might also have influenced him in adopting Sanskrit as the medium of education in this school,” Kureethara wrote.

A teacher from Thrissur’s Warrier community was brought to the school to teach Sanskrit. This was one of the earliest recorded instances of Dalits (then called Untouchables) being formally allowed to learn Sanskrit in Kerala. In the middle of the 19 century, the small town near Kottayam had a mix of students that included Catholics studying at the monastery, caste Hindus from the nearby areas and Puliyars, a community that had been classified as outcastes.

“Saint Kuriakose was the first Indian who not only dared to admit the Untouchables to schools but also provided them with Sanskrit education which was forbidden to the lower castes, thereby challenging social bans based on caste, as early as the former part of the 19th century,” Kureethara wrote.

With the success of the school, Chavara opened a school in the neighbouring Arpookara village, and his initiatives began to get noticed among the Catholic community.

In both the Mannanam and Arpookara schools, children were given school materials and a noon meal free of cost. This was the inspiration to the midday meal scheme that C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer recommended for implementation in all government schools in Travancore in the 1930s.

The scheme that has now been implemented across India has been a major factor in improving school enrolments.

In 1861, Archbishop Bernardine Baccinelli of Verapoly issued a famous circular calling for the opening of schools attached to every parish in the Archdiocese. The circular, which was drafted by Chavara, called for parishes that do not open schools to be closed down, leading to a revolutionary spread in education across Kerala.

Over the next century, social reforms were implemented by all the major religious communities in the state. Narayana Guru fought against caste-based discrimination, while Vakkom Moulavi dedicated a large part of his life to bringing modern education to Muslims, particularly Muslim women in the state. It’s a collection of these reformers and their movements that made Kerala the most literate state in India and helped educated Malayalis succeed in different parts of the world.

Sainthood

Chavara, who passed away in 1871, dedicated his life to the church and social service, and was instrumental in the concept of churchgoers donating rice for the needy.

He wrote extensively about the day to day life in his monastery and the wider society. The Mannanam Nalagamam provides a rare and fascinating Malayalam account of life in a small Christian village in the middle of the 19th century. He also established a printing and publishing house, becoming the first Malayali to do so without assistance from foreigners.

Chavara was conferred sainthood by Pope Francis in 2014, becoming the first canonised Indian male saint.

(The writer is the author of 'Globetrotting for Love and Other Stories from Sakhalin Island’ and 'A Week in the Life of Svitlana'