Column | Looking back at the Calicut of Zheng He and Ma Huan

Mail This Article

Walking at sundown on the beach in the city that is still affectionately called Calicut by many residents, one wonders how the place would have looked like when it was a major international trade hub. Six centuries ago, before the arrival of the Portuguese altered the history of Asia, trading missions and merchant ships from the Arab world and China were a common feature in Calicut.

Maritime links between modern-day Kerala and China were believed to have been established around the first century before the Christian era. China sourced almost all of its pepper from the Malabar coast by the 9th century CE. For Ming Dynasty China (1368-1644), Calicut would become a major economic centre.

A lot of what we now know about 15th century Calicut is largely because of the expeditions of Chinese diplomat, admiral and explorer Zheng He, who commanded seven voyages from China to India and beyond. Zheng’s translator Ma Huan, who visited Calicut in 1421 and 1431, documented what he saw in the city, which he called “the country of Ku Li.”

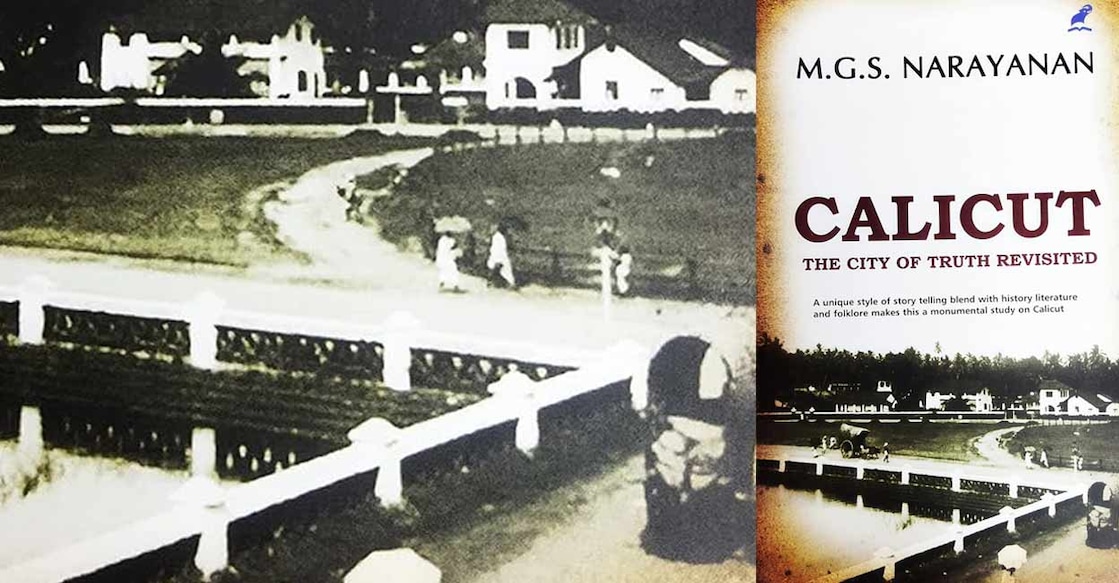

“The seaport, of which Ma Huan gives us a lengthy account, is described as a great emporium of trade frequented by merchants from all quarters,” historian M G S Narayanan wrote in his book 'Calicut. The City of Truth Revisited'. Some of the expeditions had more than 300 ships, and the Chinese visitors would stay in Calicut for about four months on these visits.

“Foreign ships from every place come there; and the king of the country also sends a chief and a writer and others to watch the sales; thereupon they collect the duty and pay it to the authorities,” Ma wrote.

Ma took note of the food and drink habits of the people of Calicut and seemed to be particularly fascinated with something quintessentially Malayali: “The coconut has ten different uses. The young tree has a syrup, very sweet, and good to drink; (and) it can be made into wine by fermentation. The old coconut has flesh, from which they express oil, and make sugar, and make a foodstuff for eating. From the fibre, which envelops the outside (of the nut) they make ropes for ship-building, The shell of the coconut makes bowls and makes cups; it is also good for burning to ash for the delicate operation of inlaying gold or silver. The trees are good for building houses, and the leaves are good for roofing houses.”

Reading his descriptions of the “wine,” one can only imagine groups of homesick Chinese in Calicut enjoying some toddy under the shade of a coconut tree.

Ma’s descriptions also give us a fair idea of what our ancestors ate before the arrival of potatoes and tomatoes with the Portuguese. “For vegetables, they have mustard plants, green ginger, turnips, caraway seeds, onions, garlic, bottle gourds, egg-plants, cucumbers and gourd-melons- all these they have in (all) the four seasons (of the year),” he wrote. “Their onions have a purple skin; they resemble garlic; they have a large head and small leaves; (and) they are sold by the chin weight.” This measure is believed to be around 600 grams.

“The king of the country and the people of the country all refrain from eating the flesh of the ox,” Ma said. “The great chiefs are Muslim people (and) they all refrain from eating the flesh of the pig.” The Chinese traveller said there was once a sworn contract between the king and the Muslims of Calicut saying, “You do not eat the ox: I do not eat the pig; we will reciprocally respect the taboo.” He added that this was honoured.

Ma mentioned red and white rice, adding that there was no wheat or barley grown in the area, adding that wheat flour came there from other places. He added that the people ate peafowl, deer and hare, as well as seafood, which was cheap.

Ma and Zheng seemed to be fond of the inhabitants of the Malabar coast. “The people are very honest and trustworthy,” Ma wrote. “Their appearance is smart, fine and distinguished.” Under Zheng’s command a stone tablet, which said, “Though the journey from this country to the Central Country is more than a hundred thousand li, yet the people are very similar, happy and prosperous with identical customs.”

The arrival of Zheng’s expeditions was a welcome event in Calicut, and the Chinese were happy to use it as a base to travel further West and explore the Arab world, Persia and Africa.

Zheng undertook his seventh great voyage at the age of 60. His fleet visited Calicut twice during the expedition, first on its way to the Gulf and Africa and then when it was returning home. “By then Zheng He was 62 years old and fell gravely ill due to overwork,” Jienan Wang wrote in the book 'Zheng He’s Voyages to the Western Oceans'. “At the beginning of the fourth lunar month in 1433, this great navigator who had devoted almost 30 years to his craft, passed away on his gorgeous boat on the sea near Calicut on the west bank of South India.”

He was buried at sea off the Malabar coast. Widely regarded as China’s greatest admiral, his Calicut connections are a great cause of celebration between the two ancient civilisations of Asia.

Today, there is hardly a trace of those vibrant days of the 15th century, when Calicut was one of the most important trading hubs in the world. But when one looks at the setting sun by the Arabian Sea, the moving waves conjure up images of Chinese and Arab fleets and seafarers descending on the city to sell their products and buy what Kerala had to offer the world.

(Ajay Kamalakaran is a multilingual writer, primarily based in Mumbai)