Some days ago, when the ball-tampering scandal involving Australian players was getting plenty of media attention, a reader of this column sent a message requesting whether I could write about instances of positive sportsman spirit which I had come across. The point made by this person was that we give publicity to bad and wrong actions by keeping on talking about it, while we hardly speak about good gestures. Unless we make deliberate efforts to give coverage to and promote acts of sportsman spirit, how would the younger generation know there are such aspects that are worthy of emulation? This sounded interesting and set me thinking on this topic.

In cricket, since the primary aim of the fielding side is to get the batsmen dismissed and an appeal is required in the process, the first form of gamesmanship is invariably excessive appealing. Almost all fielding sides keep appealing even when they know that the batsman is not out. This is done more to keep the pressure on the batsman and to keep themselves motivated rather than pulling a fast one on the umpire. But there would be instances when at least some of the players believe that batsman was dismissed while the umpire thinks to the contrary. Hence, in the matter of appealing, it is very difficult to lay down any norm for sporting behaviour, except for stating that players should accept the decision of the umpire in good spirit and with grace.

However, batsmen can contribute to improving the norms of sporting behaviour substantially by “walking” when they know that they have been dismissed rather than waiting for the umpire to make the decision. In my experience exceeding two decades of umpiring in first class matches in the country, there was only one instance when a batsman walked without waiting to see whether I would declare him out.

Parmar's principle

The batsman was Mukund Parmar, who was captain of Gujarat and this incident took place in the Ranji Trophy match against Saurashtra in 2001-02 season. Parmar played forward to a ball that spun sharply into him and struck his glove and pad before being caught by the fielder at forward short leg. Even as the Saurashtra fielders rose in appeal, Parmar walked, without even looking in my direction. Later, at the close of the match, I asked him about his action and he said, “I have always played cricket this way by walking when I knew I was out. I know that these days very few batsmen do this but I prefer to continue like this”.

It is a fact that these days, as a rule, batsmen do not walk when they are dismissed, and instead prefer to see whether the index finger of the umpire would go up, signaling that he is out. The reasoning given for this approach is that it is the job of the umpire to decide whether a batsman is out or not and one should abide by that irrespective of whether one is actually dismissed or otherwise. Some players also add the logic that there would be instances when a player can be given out incorrectly and hence it makes sense to let umpire do the decision making. While one can understand this line of thinking, what is beyond comprehension are gestures by batsmen indicating that they are not out, both before and after the umpire gives his verdict. Such actions would rank as blatantly unsporting and against the spirit of the game.

To this writer, the height of good sporting behaviour is when the captain of the fielding side withdraws the appeal if he is convinced that a batsman has been given out incorrectly, so that the umpire can cancel his decision and recall the victim of wrong judgement. To my mind the most famous of the incidents that upheld this concept of honesty and sportsman spirit took place during the Golden Jubilee Test played at Mumbai between India and England in 1980. This was a one-off Test played to commemorate the 50th year of India’s entry to international cricket.

Gundappa Viswanath was leading India as Sunil Gavaskar, who had led India to series wins against Australia and Pakistan had stepped down from captaincy protesting against the decision of the Board of Control for Cricket in India to send the national side to West Indies for a Test series after a very hectic and tiring season. England was on their way back home after playing a three-Test series and a tri-ation limited overs tournament in Australia where the West Indies was the third side. Led by Mike Brearley, England had in their ranks such champion performers as Ian Botham, Geoff Boycott, Derek Underwood, David Gower, and Graham Gooch.

Batting first, India were dismissed for a total of 242 runs as none of the top batsmen could score even a half-century despite getting off to good starts. It appeared that the fatigue caused by the long season and the euphoria of a series triumph over a full strength Pakistan side had sapped the energies of the players. But the Indian bowlers struck back and had England on the mat when wicketkeeper Bob Taylor joined Ian Botham at the fall of fifth wicket with the total on 58. Indian opening bowler Karsan Ghavri had accounted for Gooch and Wayne Larkins, while Roger Binny removed Boycott. Then Kapil Dev returned for a second spell and dismissed Gower and Brearley in quick succession. Thus, only Botham among the recognised batsmen remained to be dismissed when Taylor reached the middle to commence his innings.

Immediately thereafter Kapil bowled an out swinger which Taylor played at and the Indian players went up in appeal as soon as the ball settled in the gloves of wicketkeeper Syed Kirmani. The verdict from umpire Hanumanta Rao came quickly as he lifted the dreaded index finger. Taylor showed his displeasure and indicated that he had not edged the ball. At this juncture Viswanath, who was standing at first slip, went up to Taylor and asked him whether he had nicked the ball to which the dismissed batsman replied in the negative. The Indian skipper asked Taylor to wait and went to the umpire and said that he was withdrawing the appeal so Taylor could continue batting. Viswanath later said that the decision to withdraw the appeal was not his alone and that other senior Indian players had told him that he should recall the batsman since it was the Golden Jubilee Test.

But this decision backfired on India as Taylor helped Botham to rebuild the England innings and took the score to 229 before the latter was dismissed for a stroke-filled 114. England managed to secure a first innings lead of 54 runs, helped mainly by this stand between Botham and Taylor.

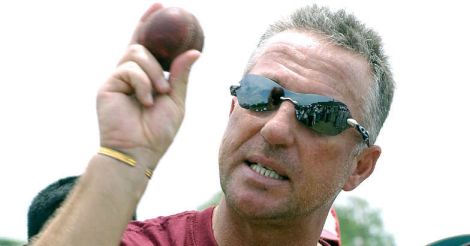

Ian Botham tormented the Indians both with the bat and ball in the Golden Jubilee Test. File photo

Ian Botham tormented the Indians both with the bat and ball in the Golden Jubilee Test. File photoBotham, however, had not finished and he ran through the Indian batting line-up to pick up seven wickets to add to his first innings tally of six. The Indian second innings ended at 149, leaving the visitors a target of 96, which they reached without losing a wicket.

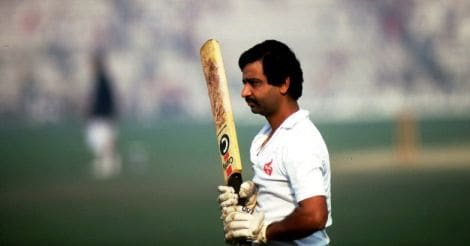

Those who knew Viswanath were not surprised by his action as he was always considered to be a walker and one who never questioned the decision of the umpire. He has gone on record that there were only two instances in his entire cricketing career when he did not walk. The first time was during a Test match against Australia in Delhi in 1969 when he was not certain whether the ball had touched the bat. The other occasion took place during a Ranji Trophy match against Tamil Nadu when, by his own admission, he was overcome by a mental block and stood rooted to his crease. He was so embarrassed by his action that he got out playing a wild shot off the very next ball.

Wrong impression

Viswanath did not lead India again after the Mumbai Test as Gavaskar was back at the helm when the next season started. Unfortunately a mistaken impression gained ground that Viswanath was too much of a gentleman to lead the country in the rough-and-tumble world of Test cricket. No one acknowledged the fact that though India lost the Test, Viswanath’s gesture in recalling Taylor earned a place in the history of the game asn a exemplary instance of demonstration of highest sporting ideals.

The relevance of Viswanath’s action and his cricketing ideals have never been higher than in present days when the damage caused to the game on account of the “win at any cost” strategy practiced by new generation of cricketers is becoming more evident. It is the humble request of this writer that such instances of sportsman spirit should be made a compulsory part of the syllabus for aspiring cricketers in institutions such as the National Cricket Academy and former players like Viswanath and Parmar should be made permanent faculty there for talking on this topic and to share their experiences. This would go a long way in ensuring that along with improving their technique and physical fitness, the next generation of players would also evolve into cricketers whose focus is not limited to merely winning the game but also to uphold the rich traditions and spirit of the game.

(The author is a former international umpire and a senior bureaucrat)

Gundappa Viswanath played the game in its true spirit. Getty images

Gundappa Viswanath played the game in its true spirit. Getty images