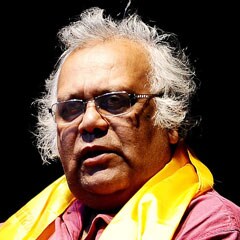

Girish Karnad - the most representative modern Indian playwright

Mail This Article

Girish Karnad (1938-2019) was one the most multi-faceted talents of India: an epoch-making playwright in Kannada, a well-known actor, director and scriptwriter for cinema and small screen, a cultural administrator who headed state and national academies and Nehru Centre, London, and so on. Though not from the backdrop of any recognisable political ideology, in the last decade or so he had become a bitter critic of Hindutva upsurge in the country.

Though he played many roles in his life, the posterity will probably remember him as the most representative modern Indian playwright. True, he wrote his works in Kannada though his plays read far better in English than in Kannada. Born in Maharashtra, raised in Dharwar, Karnataka, one of the greatest centres of Kannada renaissance in modern times, he later went to England for higher studies. He was first educated in Marathi, and his mother tongue was Konkani. His Kannada idiom was always laboured unlike that of his three peers in Kannada drama, P Lankesh, Chandrashekhara Kambar and a classic Chandrashekhar Patil. In spite of this, his signature play ‘ Tughlaq’ became a classic of modern Kannada and Indian theatre. Though he had already written his ‘Yayati' earlier, it was this second trend-setting play that made his career.

By the time Karnad began to write, modernist idiom had become established in Kannada, thanks to the poetry of Gopal Krishna Adiga, the pioneer of modern Kannada poetry. His modernism is one of angst stemming from the collapse of tradition. Karnad, like his well-known contemporaries, U R Ananthamurthy and Lankesh represented the second phase of modernism which was less about the death of tradition. It was imbued with a deep sense of irony and a certain sense of disillusionment with any reform or revolution.

Though his protagonist Tughlaq is a great visionary, all his dreams come to nought given the irremediable human condition. In spite of all his efforts to be a do-gooder, he turns out to be a monster in his own eyes. He, therefore, does not have the nobility of a tragic character. He is more a character in a theatre of absurd who is denied tragic glory. A well-made play with a tight Ibsenian plot and staccato dialogues, the play became a poetic allegory about the fiasco of Nehruvian liberal socialist project of modern India. Though Karnad has been compared to other well-known Indian playwrights like Badal Sircar, Vijay Tendulkar and Mohan Rakesh, only he was able to write a play with such allegorical power. ‘Tughlaq’ had already made a name on the Kannada stage when it was directed by B Chandrashekhara. But it was it’s brilliant Hindi translation by B V Karanth, exquisite direction by Alkazi, the legendary acting of Manohar Sigh in the lead role and the unique venue, the Old Fort, where it was staged that accorded to this play the status of a classic of modern Indian drama and theatre. If this had not happened by a happy accident, maybe this play would have been a Karnataka phenomenon like Lankesh who was an equally brilliant playwright.

Karnad was a past master in using two keys to unlock the meaninglessness of the present in his plays: history and mythology.

After the phenomenal success of ‘Tughlaq’, he wrote two historical plays based on two important moments of Karnataka history. The first is ‘Taledanda’ based on 12th century Lingayat movement of Karnataka. Its Hindi translation ‘Rakt Kalyan’ was produced on stage by Alkazi for the National School of Drama before it was staged in Kannada. Another historical play ‘Dream of Tippoo’ was first written for BBC Radio before being adapted to stage. ‘Taledanda’ was less about the reform movement than about the emperor Bijjala and his inner dilemmas. Both he and the hero of his Tippoo play were the reincarnations of Tughlaq at other times. The same is true of Ramaraya, the hero of his last play ‘Rakshasatangadi’.

His other plays like ‘Yayati’, ‘Nagamandala’, and ‘Agni mattu Male’ turn to mythology and folklore for their plot. Well-constructed like his other plays, they all rivet upon his favourite theme: fragmentation society and split of the human soul which promises neither salvation nor revolution.

Karnad’s life was a series of happy accidents. No other Kannada writer got his kind of name, fame and influence at such a young age. His entry into cinema in the 70s gave him greater exposure to the public. Though his cinematic journey began with alternative cinema exemplified by films like ‘Kaadu’, ‘Samskara’, ‘Vamshavruksha’, the exemplary modernist talent became part of commercial cinema nicknamed by our academic apologists as a popular cinema.

His huge-budget film ‘Utsav’ based on Sanskrit classic ‘Mricchakatikam’ and produced by Shashi Kapoor, in spite of a heavy dosage of succulent scenes, became neither a box office success nor a good art cinema.

Karnad is perhaps the most discussed and widely researched Indian dramatists. Countless dissertations have been produced on his works in Indian universities, particularly English departments. He is also the most celebrated Indian playwright abroad. The biggest literary and film awards came his way.

After his passing away, tributes have been pouring in extolling his achievements. But sooner or later, when we become reconciled to the inevitable fact of his death, I am sure, there will be more objective re-evaluation of his contributions to several fields of culture.

(The author is a leading poet and playwright in Kannada. He is also a professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi).