Timber at the core of his art, architect Mahesh starts documenting Kerala’s old temples now

Mail This Article

Ten minutes into any conversation, architect N Mahesh’s fingers would start twitching and he would then lunge for pen and paper to make a sketch or a drawing. No verbalisation can equal the felicity of form that emerges from his free-flowing geometrical strokes. Mahesh’s professional life has revolved around these lines, spaces, angles and dimensions.

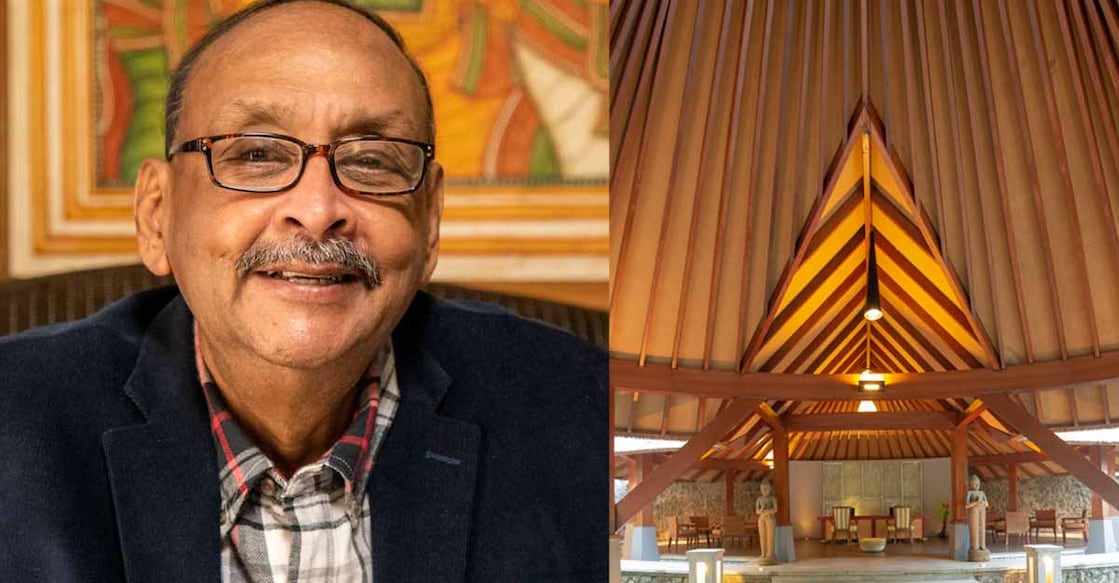

One of India’s foremost architects, the Thiruvananthapuram-based designer represents both rootedness and change, the traditional and the contemporary, beginning his career under the watchful gaze of the late Charles Correa, on the beaches of Kovalam, where he oversaw Kerala’s first five-star property come up.

Having designed some of the most avant-garde of buildings as well as, what he chooses to describe as “classic-vernacular” at the other end of the spectrum, Mahesh is now on a journey to document the architecture of the ancient temples of Kerala using “Lidar”— a digital 3D laser scanning and modelling being used in the State, unprecedented for this purpose.

Timber is what has drawn Mahesh to this latest pursuit. And that is not fortuitous. Throughout his professional life, he has persevered to adapt timber to his designs and create a unique style. The signature-tune of the Mahesh manifesto in architecture, therefore, is wood which sets him apart in the esoteric world of contemporary architecture.

“Unlike steel and cement, timber is cradle-to-cradle material, considerate of life. And indeed, future generations. Through reforestation and afforestation, we can restore the balance of timber and wood. Most people don’t realise that concrete and plastic are almost similar in their environmental impact. We often talk about plastic alone,” remarks Mahesh who in his professional journey of nearly 50 years has designed such iconic resorts like Tea County, Munnar, Diane Reef Beach Resort, Mombassa (Kenya), The Tamara Coorg, The Tamara-Kodaikanal and the Ananta Spa & Resorts at Pushkar. The Kodai assignment is particularly close to his heart, as the leisure space has been refashioned out of a 180-year-old dilapidated Jesuit monastery.

Counter-intuitively, it is sustainability that reigns when he uses wood — in a few world-class resorts designed by him, he has used the humble coconut rafter in abundance, a vernacular fixture of old tiled houses in Kerala. In that sense, Mahesh is an architect’s architect, raising timber use to an entirely new dimension and higher plane often in contemporary style.

It is the timber factor in temples that naturally fascinated him. At the age of 70, Mahesh’s passion for preserving classic Kerala temple architecture was also kindled by the scholarly 1978 tome “An Architectural Survey of Temples of Kerala”by H Sarkar and the district-wise monographs on all temples compiled by S Jayashanker, a former Deputy Director of Census Operation, during the last two decades.

“We have a distinctive Kerala form of temple structures, manifest in the dominant high-domed Sreekovil (the sanctum-sanctorum), the sloping rooflines, lavish utilization of stone and laterite, abundance of timber in the super structure, the relative capaciousness of the roundabouts, the ornate features and even the cornices,” says he. “Our temple architecture has a non-negotiable quality about it which very few people understand. As a result, many of the present-day steel and concrete modifications in our places of worship end up vandalising our past.”

His team has already captured the coordinates and 3-D images of a few temples like the more-than 1000-year-old Kanthallur temple at Chalai, the 800-year-old Kazhakkoottam Mahadeva Temple, both in Thiruvananthapuram and five other divine edifices.

“This project is quite unlike the other work that I have done so far. There are more than 38000 temples in Kerala and mindless restoration or readaptation has marred our heritage which is quite different from Dravidian architecture, whereas you can see, the huge Gopurams dwarf the structure inside. In Kerala, we find actually the converse of this style,” elaborates Mahesh.

“According to our custom, the Aasaari (the wood craftsman) headed by a Perunthachan (head carpenter) enjoys the pride of place even when we build a house. The foundation stone (a part of masonry) for any house or project is even now laid by him and timber is used by us in a sustainable way almost as a sacred material. In fact, before we cut a tree, we utter prayers to seek permission and pardon. Simultaneously, we plant afresh so that there is no net impact environmentally”, Mahesh says.

Timber, laterite and granite have been the building blocks for most Kerala temples and his project aims to preserve these footages for history. “When I undertook this journey, I realised how careless we are about preserving our temple structures in their pristine form. Painting over wooden surfaces, nailing, soot deposit and oil spills have all marred the finer details very diligently crafted, several hundred years ago. Restorative or readaptive solutions are what we require,”Mahesh’s words reflect his deep-rooted commitment to the cause he has undertaken.

His team of five led by Prof J Jayakumar of CAT intends to complete the temple documentation exercise within a year and publish it. It is common knowledge that modifications and changes to temples like construction of gopurams, pilgrim shelters and even donation boxes are done unmindful of the temples’ overall design. They end up devastating the “art forms” that temples actually are.

Author-historian M G Sasibhooshan and veteran documentarian Jayashanker are on hand to help Mahesh in the historic inputs required for this labour of love. “This work fits in well with the conceptual work that I do now, more than commercial assignments. This is also an opportunity for me to mentor young practitioners in the field,” Mahesh sums up, “it is my plan to enlist the support of the conservation experts among our professors in College of Architecture for this delicate task”

As LIDAR technology comes to the aid of documenting, monographing and thereby preserving Kerala’s corpus of architecture dedicated to divinity (read temples), it will also be a tribute to a much-forgotten man on the State’s artscape and Mahesh’s great grandfather — the late K. Narayana Iyer, who founded the College of Fine Arts in the capital during the reign of Sree Moolam Thirunal, the then king of Travancore, in 1888.