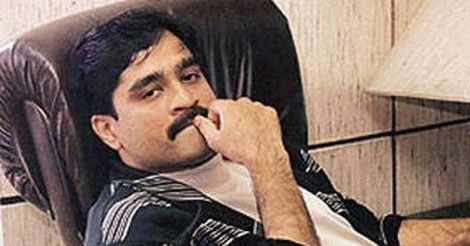

Dawood Ibrahim. The name freezes the blood of many these days. Drug lord. Terrorist. Killer. Extortionist. India’s enemy No.1. The most wanted man. And much, much more. But I had met a different Dawood more than 35 years ago. He was then trying to be the master of his own destiny after some years as a small-time associate of Haji Mastan.

The world changed for Dawood on the night of February 11, 1981. A little after midnight, brother Shabir Ibrahim was gunned down as he drove into the petrol pump near the Sidhivinayak temple in Prabhadevi, Mumbai. Chitra, a Kennedy Bridge dancer, was with him in the car. She escaped.

Ibrahim’s killing was masterminded by Dawood’s friends-turned-rivals Amirzada and Alamzeb in revenge for the murder of their gang members. Amirzada and Alamzeb were also jealous of the future don’s success after he left Mastan.

Dawood down with gangrene? Chhota Shakeel says no

The echoes of the gunfire near the Sidhivinayak temple rudely woke up the media the next morning. It sensed that a new gang war was about to drown Mumbai. At that time I was a lowly sub-editor working for Current.

Ayub Syed, the editor of the weekly, called me into his office and ordered: “Go, get the story.”

It was a Friday evening. “Come to the office only on Monday.” He then stressed. “With the story.”

He removed Rs 200 from his wallet and gave it to me. “This is for expenses,” he continued. “Don’t come to the office without the story.”

I was flummoxed. I had never done a crime story before. And this seemed to be a major one. What should I do?

With the Rs 200 – a princely sum in those days because a vada pav cost just 30 paisa -- I went to friend V. Menon’s house. We went out for dinner and discussed ways to get the story. The next day and the next, which was a Sunday, Menon and I discussed the same subject. Finally it was decided that I would go right into the lion’s lair – Dawood’s house in Pakmodia Street in the Dongri area of Mumbai.

On Monday morning, with the tentacles of raw fear tightly gripping my heart, I knocked on the main door of Dawood’s nondescript building in a cluster of ancient structures in the narrow Pakmodia Street.

“Aap kaun?” asked a young fellow.

I hesitantly told him I was from the press, from Current, which was a well-known tabloid at that time.

“I want to meet Dawood in connection with the murder of Shabir,” I added.

He asked me to wait. About 30 minutes later, a guy of medium height, neither fat nor slim, emerged from an inner room and came up to me. Dressed in a cream-coloured shirt and trousers, he had a wheatish complexion.

“I’m Dawood,’ he said, gently rubbing his moustache. Leading me out of the building to a restaurant nearby, he told me to sit at a table near one of the many doors. He too sat down and ordered tea. Affable and talkative, he rarely smiled while telling me about the rivalry between his and Amirzada and Alamzeb gangs. “We were friends once. Amirzada and Alamzeb had even attended my wedding,” Dawood said.

We conversed for an hour over numerous cups of extra sweet tea. I noticed four others lurking outside the restaurant. They were there to protect him. I finally decided it was time to leave.

As I shook hands with Dawood before leaving, he said he wanted to see the story before it appeared in print. I said I would tell my boss.

The next day, I met Dawood with the typed story at the restaurant where I had met him the previous day. One of his friends read it and said it was fine. And I asked him for a picture.

Leaving me at the restaurant, Dawood went home and returned with a black and white picture of him with Alamzeb, Amirzada and contract killer and extortionist Samad Khan. This picture taken at Dawood’s wedding was later used many times in the print media.

Dawood then asked me if my boss had approved the story. I replied in the negative. He said that two of his men – one was Masoom Fighter—would accompany me in a taxi hired by him and would wait at the Current office until the story was okayed.

Scared to the core, I prayed Dawood’s rivals would not open fire as our taxi moved through the crowded road from Dongri to Nariman Point.

Syed was not in the office on the 15th floor of Nariman Bhawan. So I asked Mohan Rao, the deputy editor, to okay the story fast as Dawood’s men were waiting outside to know if any changes would be made.

Rao quickly read the story. He said the story and the picture, both scoops, were fine. The story was front-paged in Current the following week and it got a lot of praise. Fast forward to 1984. October 3. Samad Khan, a nephew of Karim Khan aka Karim Lala, now a member of the Alamzeb-Amirzada gang was gunned down. Dawood was recognized as one of the killers. The killing was the climax of a blood feud between the Dawood and Amirzada-Alamzeb gangs. The reverberations of the killing were felt in the media, among the police and in the underworld.

I was then working for Onlooker magazine. Yogesh Sharma, my editor, asked me to do a cover story. With the help of Sharafat Khan, an Urdu journalist, I got dramatic stuff. But relevant pictures were most important. Khan told me he knew Dawood’s family photographer – I don’t remember his name. Enquiries revealed he had gone to Pakistan to visit relatives.

Khan said the photographer’s brother Javed Ehtesham could be approached. In his late teens, the wiry Javed was impressed with my offer of Rs 15 for each printed picture. There would be bylines for all the printed pictures, I added.

Without any hesitation, he showed me numerous colour negatives from his brother’s library. I selected a number of them. Soon, I had the colour prints made from the negatives. And I went to the Onlooker office with a song on my lips. When he saw the pictures, Yogesh too had a song on his lips.

The story that appeared in the October 23-November 7 issue of Onlooker with the exclusive pictures was a big hit. Then the sky came crashing down on my head. On a balmy morning about three days after the magazine hit the newsstands, I reached office and plunged into my work. In came Sharafat Khan and Javed. “Dawood wants to see you,” said a grim Sharafat. “You have to come with the negatives of the pictures.”

I hesitated.

“You have to come with pictures,” pleaded Sharafat. “Or else they will kill Javed.” Javed was bleary-eyed. He seemed close to tears. Perhaps he was staring at death.

I went to Yogesh and told him everything. He warned me against going to meet Dawood. But I was adamant about going. He relented and told me to get the permission of GL Lakhotia, the general manager, to take the pictures and negatives. Lakhotia was hesitant. When I told him of Dawood’s threat to kill Javed, he gave his nod.

By noon, I was at Dawood’s home with Javed and Sharafat. I was separated from them and led by one of his cronies to a square room with dark glass walls on two sides and normal brick walls on the other two sides.

The long wait to meet Dawood began. Hours passed. Lunch came, followed by tea. Sensing that I was being watched from the other side of the dark glass walls, I tried to behave normally, without exhibiting any kind of fear.

There was no sign of Dawood. The suspense was unbearable. Finally around six, a short, fair guy walked in. He said his name was Babu.

I asked for Dawood.

“Dawood is busy,” he replied. “He will not see you.” I was a bit disappointed.

Babu asked me for the pictures. I handed them over.

“Did our rivals give you the story?” he asked.

“I got it from my contacts with Sharafat Khan’s help. The police also helped me. ” ”The pictures?” he asked.

“I promised Javed some money for the pictures. I also told him that his name would appear besides the pictures in the magazine,” I replied.

Satisfied with my answers from which it was clear that I was not working for Dawood’s enemies, he permitted me to leave.

Once outside, I went to the nearest public phone and dialled Yogesh. I could sense the relief in his voice as he said: “I am still in the office, waiting for you.”

After briefly telling him of my experience at Dawood’s place, I kept the phone down. As I waited for a bus outside JJ Hospital to take me home to Antop Hill, there was once again a song on my lips.

(The author is a journalist who has worked in India and abroad. His motto: Have a good laugh at everything and that will make your day. The views expressed are personal.)