Column | India’s first diplomatic martyr

Mail This Article

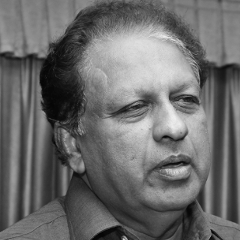

Long before terrorism and violence became the hazards of diplomatic life worldwide, a young Indian diplomat fell victim to an assassin’s bullet in his office in the High Commission of India in Ottawa, Canada, on April 19, 1961. Kokkat Sankara Pillai (KSP) of the first batch of the Indian Foreign Service (IFS) had arrived in Ottawa six months before as the Deputy High Commissioner after having served in Colombo, Port of Spain (Trinidad and Tobago), and New Delhi. Seeing an unexpected visitor at the door, KSP got up from his chair to shake hands with him and the assassin shot him point blank and killed him instantly. KSP did not know who the assassin was and why he shot him. The man walked undetected out of the High Commission and went to a police station and surrendered.

It turned out that the man had come earlier to the High Commission to seek a visa and a work permit for India. The Consular Assistant found out that he was blacklisted in India and stamped “Visa Applied For” (VAF) on his passport and returned it to him. When he discovered later that the VAF stamp amounted to denial of visa, he returned to the High Commission with a rifle to shoot the Assistant, but in his absence, shot KSP. Only a mad man could have committed such a heinous crime. After expressing deep regret over “the death by shooting of one of our distinguished younger members of the Foreign Service,” Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru stated in Parliament that “such facts as we have apparently indicate no motive except that some person who is rather demented”. He also read out the message from the Indian High Commissioner in Ottawa, which stated: “We are all shocked at the tragic end of a brilliant officer. The shock will be terrible for his wife who is expecting a baby.” The assailant, a Canadian of Yugoslav origin, Shani Ferizi was tried and sent away to a mental asylum for several years.

Tragic news

I remember April 19, 1961, evening very well. We were at the Kakkanad Temple near my village home at Kayamkulam for a festival. The news came like a bolt from the blue that the most famous son of the area fell to an assassin’s bullet in Ottawa. A pall of gloom descended on the gathering. For many people assembled at the temple, KSP was, more than a diplomat, the eminent son of the Kokkat family and even more, the son-in-law of Ambalappattu Damodaran Asan, who was the lord and master of the whole area.

My father was most upset as he had known and admired KSP as a brilliant young lecturer in the University College, preparing for the UPSC examination, which placed him in the elite IFS in 1948. Those were the days when Pandit Nehru personally interviewed every candidate selected for the IFS and handpicked some like K R Narayanan and a few from princely families. My father was so impressed with him that he wanted me to take him as a role model and aspire to join the IFS and become an ambassador one day. He would tell me how KSP would bring half a dozen books from the University College library every evening and return them the next day. Initially, I took it as an idle dream of a father, who thought that his son could move mountains and set it aside. I was only four years old when KSP joined the IFS!

Role model

My father sent me to the University College, though he had cheaper options of sending me as a day scholar to one of the neighbouring towns. He insisted that I should literally follow KSP’s footsteps. The sudden passing away of KSP, when I had just entered the University College, shattered my father, but instead of abandoning his dream on that account, he made it his mission to make me fill the void left by KSP in the IFS and in our society. Fortunately, the gamble succeeded and I joined the IFS in 1967. By then, KSP had become a legendary star on the diplomatic firmament of India and people spoke of him in awe and admiration. All who knew him as a colleague said what a big loss it was for India that he died in his prime.

Taking the story further, my younger brother, Seetharam, 12 years my junior, whose career guide was my academic and IFS journey, joined the IFS in 1980 and that too was because of the indirect influence of KSP. He had unknowingly created two diplomats for India.

My father’s fascination for KSP went to the extent of accepting the hazards of the IFS. After a military coup in Fiji when I was High Commissioner there, someone fired a shot at the British High Commissioner’s car and when my father heard the news on radio, he was sure that history had repeated itself till I called him.

Every achiever owes his/her success to the dreams of a father as Barack Obama stressed in his autobiography ‘A Father’s Dream’ and the children who are able to fulfil that dream are fortunate. In my case, the story goes back to KSP who ignited the dream in my father. Throughout my career and after, a prayer of gratitude for him remained in my heart, like Ekalavya for Dronacharya. I welcome this opportunity to offer him my “gurudakshina”.

The family of KSP invited friends and relatives to record their memories of him on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of his assassination. The rich literature generated on the occasion highlighted his sterling qualities and the gravity of the tragedy. But there was also a tinge of sorrow in one of the tributes that the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) did not allow his body to be brought back even though his parents were alive. Further, the MEA informed the family that arrangements for their arrival in Mumbai should be made by them. The Manager of the Central Government Guest House was the only official at the airport. “It is surprising that even after 14 years after Independence, an event of this magnitude catching the attention of the of the top-most administrators, including the Prime Minister of India, was treated so callously by the powers that be,” he wrote.

A young IFS colleague discovered that the Annual Report of MEA for 1991-92 has recorded the tragic incident in a bland manner, without any expression of condolences or the loss sustained by the Ministry. It said, “The First Secretary, Shri. K Sankara Pillai, was shot dead while in office on 19 April, 1961, by one Shani Ferizi, a naturalised Canadian national of Yugoslav origin. The assailant was tried by a Canadian court and has been sent to a mental hospital.” This insensitive entry of a tragic event is hurtful even now.

As India's Acting High Commissioner in British West Indies, KSP had presented 24 copies of the Bhagavad Gita to the Chief Justice of Port of Spain on February 8, 1956, for use in the Law Courts of the island. "The Bhagavad Gita that Pillai presented to the Chief Justice had several slokas that dwell on the inevitability of death and profound counsel to surviving family members and friends to cope with the grief," wrote K Vijayakrishnan in 'Madras Courier'. Even now, they must be finding solace in the words of Lord Krishna.

(The author is a former diplomat who writes on India's external relations and the Indian diaspora.)