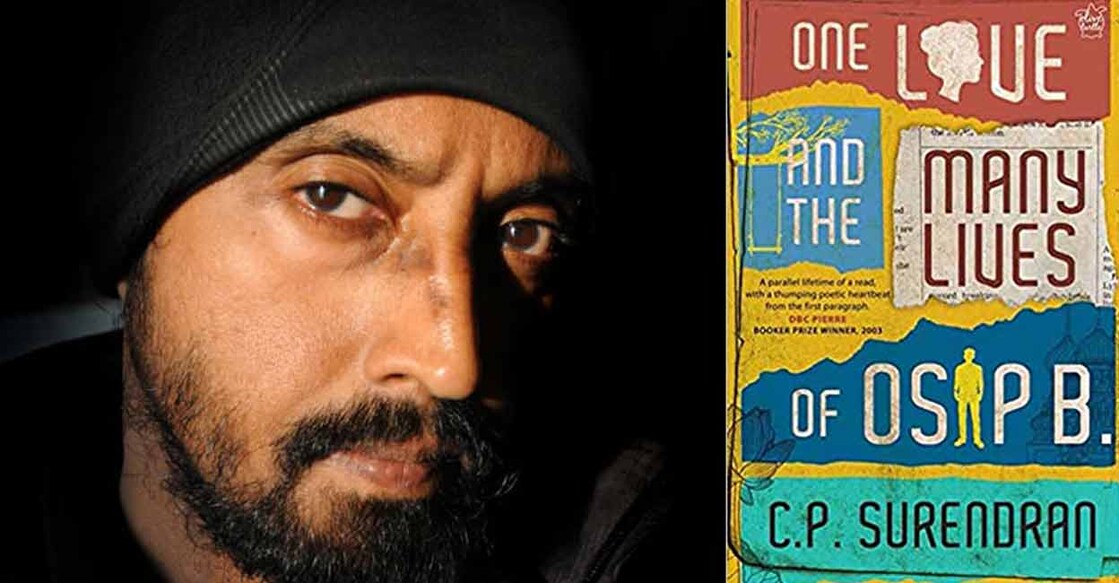

Ghosts of Stalin and #MeToo in a B/W (brown and white) love story | Book Review

Mail This Article

On the face of it, poet and journalist C P Surendran's latest work of fiction 'One Love and the Many Lives of Osip B' is about the adventures of a lovelorn 'maladjusted boy of 18', an orphan brought up by an old couple, who plots a spooky kidnapping to find the money to fly to England to woo back his love, his white English teacher who had slipped back to her country shaken by the shame of their affair.

But events in the book need not be as it seems. The narrator, Osip B has a mental disorder, a disturbance of the mind he shares with his grandfather, the old man who adopted him. Both of them hallucinate.

For instance, they occasionally come across Stalin, the very Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin of the walrus moustache and the murderous purges, and Osip Mandelstam, the poet he had banished to Siberia for not falling in line. Osip has even seen Prime Minister Narendra Modi travelling in an autorickshaw.

Therefore, Osip's version is highly unreliable. They could have happened only in Osip's diseased mind, for all we know. He could have thought all this up while semi-circling in the old swing tied to a barren mango tree at the back of his grandfather's house in Thrissur, contemplating suicide.

In fact, Osip B (Bala Krishnan) was named after Mandelstam by the hallucinating grandfather, Niranjan Menon, a top Communist leader in Kerala and a Stalinist in his own right. Though a Stalinist, and the killer of 23, Menon had grown to despise Stalin and had once spat at the leader's bust in Moscow.

Menon had possibly named his adopted child Osip as yet another way of getting back at the man who engineered the famines and purges in the Soviet Union in the late 1930s.

Osip the First would have withered away in the vast snowy wilderness of Siberia but while naming his adopted son Osip, Menon would have vowed that his boy would not be held back. Osip the Second would be the daring iconoclast the first was not allowed to be. His child was to be the triumphant sequel to Osip the First.

The grandfather's readings from history books and his disillusionments would have fired the imagination of little Osip. The bizarre events, most of them unlikely coincidences, that litter the 370-odd pages of Surendran's book could merely be Osip II's desperate wish or his mind's way of living up to his grandfather's iconoclastic ideal, or both.

It has to be said that some of these chance happenings are so B-grade at heart. Meaning, these are plot points that filmmakers with no claims to artistic virtuosity employ to conveniently propel a story forward.

A teenage school drop-out's quick friendship with a known columnist (modelled on Surendran himself), the protagonist stumbling upon his grandfather's brother right in front of him at an English pub, a rebounding wine glass shard magically gouging out just the cataract from a diseased eye, a pretentiously servile Uber driver reemerging randomly at the climactic moment as a right-wing tormentor... These, therefore, can be seen as further proof that the B-grade mind of the disturbed teenager is making things up.

Nonetheless, quite in tune with the working of an abnormal mind, Surendran seeks to summon up a sense of timelessness in the novel. The past, present and the future flows so chaotically into each other – colliding, scattering, mixing – that it is hard to know which period's waters are lapping at your feet at any given time.

It is almost like being surrounded by the Ocean of Time, where all that happened, happening, and are about to happen exist at the same time. Add hallucination to this mix.

Even characters seem to have this God quality, of having existed forever. Here is how the narrator speaks of Ava Lenk, a holocaust survivor. “Ava barely in her teens, then, cast already in the mold of a woman ancient enough to have lived through all of history.”

Osip, the narrator, is a dreamy traveller uninterested in the highway of the present. A word in the present, 'home' for instance, is enough to nudge him to take a branch road that winds deep down through the thicket of the past. Even the placement of a lover's hand can instigate him to dive deep into the hidden backwaters of memory in search of his most tender feelings.

Take this portion where Osip B finally gets to sit down with his lover, his former teacher Elizabeth, in a bar in London. Elizabeth tries to drill some sense into him, saying they will not be happy together.

‘It’s for your good, OB.’ Elizabeth places her hand on the table, palm down like a mouse. A slender beautiful mouse. In the children’s home, we would sleep on long, narrow straw mats in rows after rows, and when the lights were turned off, white baby mice would start falling from the wooden beams supporting the tiles, on our stomach, chest, face. They would just lie there quiet, tiny, helpless things with pink feet and closed eyes, and I would wonder how they found their way back to their mothers. When the mice fell, we could not make any noise though we wanted to, because big women with sticks would be walking around ensuring we slept.

The novel also revels in the personal. The larger human issues, holocaust, Aleppo bombings, Kuridish refugees, Tibetan exiles, all of these form just the context, slightly more than just a backdrop, to the wanderings of the novel's characters. In 'One Love and Many Lives...', war and exile are private concerns.

Surendran's writing is relaxed, not vigorous like Roth's or Rushdie's, but with a poetic glint. His way of looking at things could feel like a near revelation. See how he attributes a serial killer aura to a gas cylinder. The red gas cylinder stood in a corner, apologetic, shoulders rounded and sloping, but at the same time ominous; waiting.

Here is how Osip describes the way the disgraced columnist Arjun Das is seated at his study. Arjun rested the short quotation marks of his legs on a footstool. Even a photograph of Arjun seated could not have described the position of his toes better.

Though the Left excesses run almost like a leitmotif through the book, the Right is not spared. The most satiric, both damning and portentous, image in the book is that of Narendra Modi.

I step out, look up at the sodium-light drenched night sky and see over the Palika Park, the Prime Minister rise in the air in a massive white balloon. Didn’t I just see him drive away in a rickshaw? The Leader is everywhere. There is no other way for a Leader to be. The balloon is flashing-white in colour. The portrait on it is gigantic. I watch the PM rise and rise, an inflated benevolence over the capital, rising.

On rare occasions, the writing can be so trite, so unfunny, like when Surendran describes people trying to keep a distance from an unpredictable woman. She looked up at the room with its people racing away from her at the speed of light.

Surendran also betrays the original Osip. He uses his novel as propaganda, a tendency Osip Mandelstam had revolted against and had paid the price for. He paints Arjun Bedi, the disgraced journalist and his proxy, as the most tragic figure in the novel.

Arjun's character has been squeezed in almost like comedians in old films, a separate track that puts a temporary pause to the main narrative. Arjun really has no business being in this novel, except to function as Surendran's mouthpiece.

He, like the author, has been swept up and hurled into near oblivion by the #MeToo wave. Arjun, like Surendran, has been accused of misogyny, harrassment, obscene sexist remarks, inappropriate touches, almost everything short of attempt to rape.

Arjun can be heard mouthing lines we have already heard Surendran speak through his columns.

...all this ganging up and trying to muzzle me…it is not legal, it is not constitutional, and, who, who are they? Scented Saints? The French Guillotineers? The Commissars of the Peoples? A sentence I wrote, a joke I cracked—I know you won’t believe me—is the most traumatic event in the life of some woman, or man, as the case may be, waiting to be outraged? Nothing more painful has happened in their lives besides this…this breach of drawing room decorum?

He sounds both helpless and bitter. If we can somehow ignore the overwhelming sense that Arjun is here to make Surendran's case, what happens after Arjun's terminally ill wife crashes the party her husband has thrown for the high and mighty could come across as the most poignant moment in the novel. Osip's neurosis comes nowhere near.