What should Western Ghat states, including Kerala, learn from Uttarakhand glacier burst?

Mail This Article

Experts will investigate what triggered the February 7 disaster in Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district, described in Parliament by Union Home Minister Amit Shah as a snow avalanche caused by a landslide that led to a flash flood in the Rishi Ganga river downstream, but one thing is sure – landslides have routinely wreaked havoc across many parts of the country, especially the Himalayan region, since Independence.

In 1948 a landslide caused by heavy rains claimed over 500 lives in Guwahati, while in 1968 torrential rainfall unleashed multiple landslides, breaching the Darjeeling-Sikkim road link at more than 90 places and killing thousands of people. More recently, a series of landslides wiped out an entire village of nearly 400 residents at Malpa in Uttarakhand in August 1998, while 68 people lost their lives at Ghatkopar in Mumbai in July 2000.

The Kedarnath tragedy on June 16, 2013 shook the entire nation with landslides in the Himalayas causing rivers and lakes to burst their banks, killing nearly 6,000 people and causing devastation across hundreds of villages and towns.

Around 150 people died and a 100 went missing in a deadly landslide at Malin in Maharashtra’s Pune district on July 30, 2014. The landslide transformed the picturesque village in the Sahyadri hills into a corpse-strewn mud wreck.

In Kerala, 58 plantation workers were buried alive at Pettimudi in Kerala’s Idukki district on August 7, 2019. The state reportedly lost 63 people in the landslides at Kavalappara in Malappuram and Puthumala in Wayanad districts.

Landslide-prone areas

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) lists the Himalayan states, Meghalaya plateau in the north-east, Western Ghats and Nilgiri hills as most landslide-prone areas in the country. Roughly 15 percent of India’s landmass is highly vulnerable to landslides, according to the Geological Survey of India (GSI).

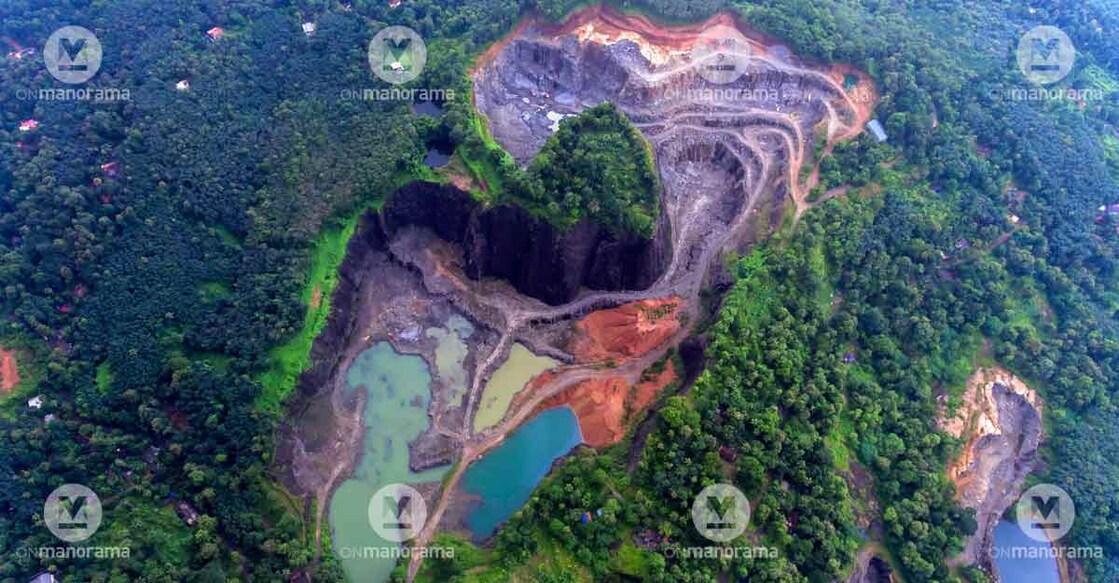

Geologists define landslides as “a natural phenomenon causing the downward and outward movement of slope materials like rocks, soil and so on under the influence of gravity.” They mostly occur during the monsoons (June to September) when excess rainwater pushes the soil triggering a chain of events intensified by man-made activities like mining, construction and deforestation.

The latest disaster in Chamoli has once again shifted the spotlight back on this recurring menace, which is not always due to natural causes.

‘Failure analysis of Malin Landslide’, a study by Professors G L Sivakumar Babu and Pinom Ering from the Geotechnical Engineering division, Department of Civil Engineering of Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, shows that though heavy rainfall was considered as the triggering factor for the disaster, human activities such as deforestation and improper land use planning also contributed to the slope failure.

Amongst all other factors that trigger a landslide, rainfall is the easiest to quantify correctly, hence there is a tendency among the lay persons and even some so-called experts to blame it for landslides. But there are other factors. The villagers of Malin, according to the study, witnessed signs of distress and cracks but chose to move back to the village without understanding the risk associated with it.

“It is important to perform a risk assessment of the area which involves characterisation of consequence scenarios, determining elements at risk and their vulnerability, evaluate probability of land sliding and severity of consequences. Such assessment or zoning may help people in avoiding those danger areas,” Babu and Ering suggest while noting that the disaster in Malin could have been avoided if efficient early warning systems were used.

Dissemination of alerts

There is little doubt that it is important to develop people-centric early warning systems. The handling of latest occurrence in Chamoli by NDRF and Uttarakhand administration shows that efficient communication or dissemination of alerts and warnings could save the lives of people living in landslide risk zones, though the flash floods left over 30 dead and around 175 missing, most of them working close to the two hydropower projects located close to Reni.

The fragile Himalayas – the mountain range was formed due to the collision of Indian and Eurasian plates – remain especially susceptible to landslides. The northward movement of the Indian plate causes continuous stress on the rocks, rendering them friable, weak and prone to landslides and earthquakes, say geologists.

The larger finding that emerges from the Malin study, or elsewhere, is that it is critical to treat the vulnerable mountainous areas with extreme caution. They are ecologically sensitive areas, where any mining or construction activities should be severely restricted and deforestation avoided. Road construction has been found to be especially toxic to the environment of these fragile areas as it involves rock blasting which throws the rock-soil balance virtually off the cliff, experts say.

The Indian government has identified areas where landslides occur repeatedly and also published guidelines that include tips for citizens. The contribution of a vigilant citizenry that is aware of the warning signs of impending landslides is pivotal. Also, green measures like growing more trees that can hold the soil through roots and identifying areas of rock fall as well as cracks that indicate landslides are undertaken for mitigation and management in the hazard zones, government sources claim.

Eco-Sensitive Zones

So far as the Western Ghats are concerned, the Centre is yet to finalise the notification of the eco-sensitive zones in the Western Ghats in spite of repeated directions and a recent reminder from the National Green Tribunal to complete the process by December 30, 2020.

The Centre had notified 56,825 square kilometers spread over six states – Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu – as an ecologically sensitive area (ESA) way back in 2015. The decision was taken nearly four years after the Ecologist Madhav Gadgil-led Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel recommended that the entire Western Ghats be declared as ESA since it is a biodiversity hotspot.

The onus of monitoring and enforcing restrictions in the ESAs had been placed on the respective states. But instead of accepting the Gadgil committee recommendations, several states and stakeholders, including government and private bodies, chose to oppose it.

The Union ministry of environment and forests (MoEF) constituted a high level working group under K Kasturirangan to take a relook at the report and it was recommended that 37 percent of the Western Ghats, which constitute 60,000 sq km, be declared as ESA.

The Central and state governments, keeping with their ‘privatised development’ narrative, have repeatedly been seeking more and more exclusion of eco-sensitive areas from the 56,825 sq km left as ESA now. This is being done claiming the need for ‘development’ while ignoring the urgency of ‘environment protection.’

Large swathes of the Western Ghats, much like the Himalayas, are thus being thrown open for construction of multi-lane highways, irrigation and hydropower projects etc. along with tourism and the growing demand for private farmhouses and weekend homes away from crowded cities like Mumbai and Pune.

Warnings go unnoticed

In fact, barely five years after the Malin incident and even before accomplishing the promised rehabilitation of all the survivors of the tragedy, the Maharashtra government announced the New Mahabaleshwar development project, providing the urban neo-rich with “a chance to have your own space at this beautiful location called New Mahabaleshwar – Koynanagar”.

The way Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation is promoting it, the project is expected to be a big draw among the educated, upwardly mobile class from the country’s top metros. It promises a modern hill station, “an amicable destination, offering a pleasant getaway from the hectic city life,” ironically located in the seismically vulnerable backwaters of the Koyna dam.

Many amongst the targeted population wouldn’t have heard of Gadgil or his report on the Western Ghats. And even if the odd one amongst them has, they would rather ignore or even ridicule the cautionary notes it holds. The warnings held by the recurring tragedies, whether in Uttarakhand, Malin or even Mumbai, will go unnoticed as well.

Like the hills and valleys in the Himalayas, the alluring landscape of the Western Ghat captivates one and all with its tourism and investment potential.