Pune's erstwhile LS dominance has waned, it needs a new zest

Mail This Article

In December last year, a news agency ran an alert hinting that Madhuri Dixit-Nene may be the BJP's candidate for Pune parliamentary constituency. It created a flutter in the city's political circles, though the BJP dismissed it as a rumour.

Earlier in November, NCP chief Sharad Pawar had put to rest talk about his likely candidature from Pune.

Speaking at the launch of a coffee table book reminiscing about Pune’s evolution, Pawar acknowledged the city had shaped his future politics, but 'complained' it hadn't treated him well.

He recalled, with some amusement, how he was chastised by an elderly gentleman for knocking on his doors one hot afternoon several decades ago.

"Don’t visit voters when they’re resting," the young Pawar was told before being shooed away.

It’s another matter that the typical ‘Puneri’ gentleman residing in a quiet lane on posh Prabhat Road, went on to become his grandfather-in-law.

After Pawar, it was the turn of another former chief minister, Prithviraj Chavan, whose name too was doing the rounds as a probable candidate from Pune, perhaps due to his frequent visits as in-charge of Congress’ Pune affairs.

Chavan put a full stop to the talk a fortnight ago with a frank admission: “I don’t have a base in Pune”.

Meanwhile, candidates for three (Baramati, Shirur and Maval) of the four Lok Sabha seats in Pune district have been named or nearly finalised by the rival alliances – the BJP-Shiv Sena and the Congress-NCP combines – but it’s still far from clear who will contest from Pune for either of them.

Will the sitting MP, BJP’s Anil Shirole, contest again?

The question is doing the rounds of the constituency.

Anil Shirole who? If you’re not from Pune, you may be justified in asking this question.

A former corporator and the BJP city unit chief, the courteous and soft-spoken Shirole hasn’t impressed as an MP, but looks like there’s none to either replace or challenge him.

Pune’s facing an unusual drought of candidates worthy of the Lok Sabha, ever since the ignominious arrest and expulsion of Suresh Kalmadi, a three-time Congress MP from Pune, in wake of the Commonwealth Games scam in 2011.

The NCP made brief inroads in the traditional Congress stronghold by capturing Pune Municipal Corporation in 2012, but was dislodged by the Narendra Modi wave in 2017.

After Shirole won in Pune by a whopping margin of 3.15 lakh votes, the BJP went on to capture all eight assembly seats and the civic body as well.

The Congress has been so thoroughly and completely vanquished in Pune, that it now has to borrow a candidate from outside to appear a serious contender in the Lok Sabha poll battle against the BJP.

The frontrunners are both builders, Sanjay Kakade, Rajya Sabha MP and BJP’s associate member, and Pravin Gaikwad, a member of the Peasant and Workers Party and former president of Sambhaji brigade.

They are ready to join the Congress provided they get the LS seat.

Among the BJP’s options are the city’s guardian minister Girish Bapat or city unit chief Yogesh Gogawale, or likely a surprise candidate, other than Madhuri.

Right now, they seem content with watching infighting in the rival camp.

Congress loyalists have gone public with their disappointment. They are urging the central leadership to consider someone devoted to the party, even if he or she’s an obscure entity when it comes to national, state or even city politics.

This should bother the voters – Pune registered a 10.34 per cent increase in voters, from 9.93 lakh in 2014 – scheduled to exercise their franchise on April 23.

“Pune used to boast an army of formidable contenders for the Lok Sabha, who excelled on the national scene,” veteran journalist Arun Khore said.

He recalled how Chandra Sekhar, during his tenure as prime minister in 1990-91, had jokingly complained to him about the “pressures” exerted by “Pune’s Nana and Anna” (referring to the senior socialist leader Nanasaheb Goray and fellow ‘Young Turk’ Mohan Dharia) on him, “before arriving at any important decision”.

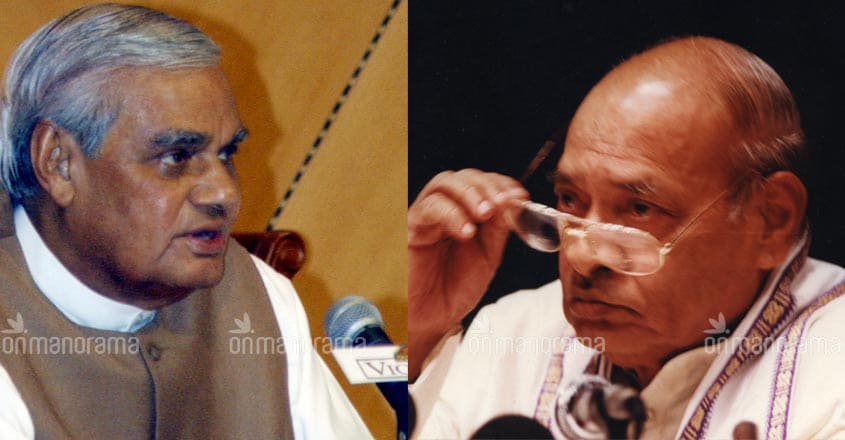

Former Prime Ministers Chandra Sekhar, Narasimha Rao and Atal Behari Vajpayee were known to maintain close ties with the city.

They also held discussions or sought advice from leading intellectuals and experts hailing from the city.

Among them were those who had represented Pune in Parliament, whether it was Dharia (elected twice in 1971 and 1977), Goray (elected 1957) or S M Joshi (elected 1967), all of whom were well-known socialists.

Within the Congress, those dominating the national scene included the father-son duo of N V alias Kakasaheb Gadgil, who was elected from Pune in 1951 and served as a minister in the union cabinet from 1947 to 1952.

His son, V N Gadgil, won the LS polls from Pune thrice - in 1980, 1984 and 1989 - and was the face of the Congress during the eighties and nineties as the union minister of information and broadcasting and chief spokesperson of his party.

At one point, the Congress monopoly over Pune was so complete that the only battles ever witnessed were between its various factions led by the Gadgils and Tilaks, descendants of the Lokmanya, and their rivals through the fifties, sixties, seventies and eighties.

The rise of the Pawar-Kalmadi factions in the nineties led to a decline of the old guard as also the tradition of intellectualism and scholarship.

Pune remained a Congress bastion and Kalmadi was elected thrice in 1996, 2004 and 2009.

Like the socialists in the fifties and sixties, the BJP managed to wrest the LS seat in 1991 and 1999 from the Congress.

The Emergency in the seventies, followed by the Shah Bano case and Ramjanmabhoomi movement in the eighties, provided the initial impetus for the rise of Hindutva in a city, where Jan Sangh, the precursor to the BJP, was known as an ‘also ran’.

The saffron surge eclipsed the socialists and other progressive movements in the city while the Congress watched its base disintegrate steadily.

The leadership did little to counter Hindutva, except may be Sharad Pawar, who turned to Mahatma Jotiba Phule, declaring his ancestral home in Pune a national memorial in 1993.

This was a clever move to appease the Bahujans or non-upper castes, but ever since the Maratha leader left the Congress to float his NCP in 1999, he faced accusations of promoting chauvinist elements from his caste.

The Sambhaji Brigade, which attacked and vandalised the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute in January 2004 prompted by the controversy over James Laine’s ‘Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India,’ is widely viewed as a by-product of Pawar’s politics. The Maratha chauvinist organisation continued to rant and rave against ‘Brahminism,’ resulting in the unceremonious removal of statues of Pune’s medieval-era administrator Dadoji Kondev in 2010, and Marathi literary icon Ram Ganesh Gadkari in 2017.

The other main contender for the anti-Brahmin plank, the Dalits could never become an electoral force in Pune, as elsewhere in Maharashtra.

As BSP founder Kanshi Ram, who spent his early formative years in Pune, observed, their selfish alliances with the Congress reduced them to mere “chamchas (stooges) of the establishment”.

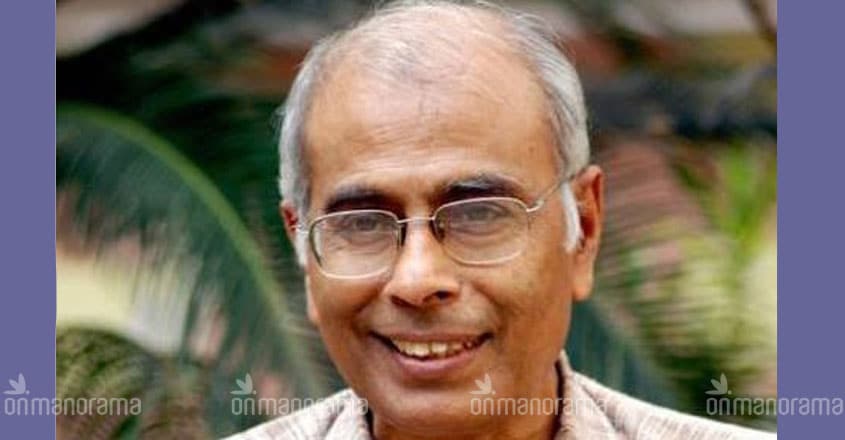

The wakeup call came with the broad daylight shooting of rationalist Dr. Narendra Dabholkar on August 20, 2013. The murder led to a widespread fear among intellectual and political circles that violent Hindu groups were growing in prominence, and muzzling free speech in a city with a long-standing tradition of progressive thought.

The city had once served as a cradle to Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Pune Sarvajanik Sabha, a precursor to the Indian National Congress, and Jotiba and Savitribai Phule’s Satyashodhak Samaj, which shaped the society and politics of Maharashtra.

It had now become a breeding ground for violent groups like Abhinav Bharat, which came into focus after the 2008 Malegaon blast, and Hindu Rastra Sena, whose followers were arrested for killing 24-year-old techie,Mohsin Sheikh, during a communal outbreak in Pune in June 2014.

The spirit of ‘Hindutva’, a term coined by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar to give his co-religionists a collective identity, had been kept alive in Pune by a committed band of followers who would gather every year on his birth anniversary at Fergusson College, where a hostel room he occupied as student during 1902-1905 remains well-preserved.

The death anniversary of the Mahatma’s assassin too was an annual occasion for members of the Hutatma Nathuram Godse Icchapatra Nyaas, to renew a pledge that his ashes will be immersed in the Sindhu river after his final wish of achieving a ‘Akhand Bharat’ was fulfilled.

The larger society’s muted response to Dabholkar’s murder and those of Communist leader Govind Pansare and Kannada scholar M M Kalburgi in their homes towns at Kolhapur and Dharwad respectively in 2015, pointed to a wider shift in the socio-political climate in the region surrounding Pune.

This shift could be traced back to Pune’s journey, from a mid-seventeenth century Maratha garrison town on the Deccan plateau to the proud capital of the Peshwas, who went on to exercise military influence over large parts of India till their defeat by the British in 1818.

The British rule left Pune with a permanent colonial stamp in the form of a military cantonment and the introduction of Western cultural and education influences.

The dominance of Brahmins began to wane by the 1930s, after over a century of British rule and two decades of intensive anti-Brahmin campaign and reforms by progressives influenced by Phule.

The Satyashodhak movement surpassed the ideologies of Tilak and Savarkar. Among its leaders were progressive Brahmins like Kakasaheb Gadgil and Marathas like Shankarrao More (elected Pune MP in 1962).

The trend continued after Independence with progressive ideologies serving as the foundation for a variety of social and political groups, educational institutes and trade unions.

Brahmins faced violent reprisals after Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination; many families in the villages and towns of western Maharashtra were forced to abandon their burnt homes and agriculture lands, and seek refuge in Pune.

By the time Maharashtra became a state in 1960, Congress’ pre-dominantly rural Maratha leadership was firmly in the saddle, though some Brahmin leaders like Vitthalrao Gadgil and Jayantrao Tilak held their ground.

Hindutva remained dormant but the RSS and its affiliates continued to expand their base through new RSS shakhas in the city’s low-income areas, or educational and social initiatives like Jana Prabhodini-Pune, founded in 1962 with focus on women and youth as new faces of a ‘Better India’.

Pune was by now well-known as a centre of educational and social reform, where modern education combined with its tradition of Brahmin scholarship had helped it earn the sobriquets – Oxford of the East and Pensioner’s Paradise.

Post-liberalisation, it emerged as a leading IT destination, and renowned centre for auto and design industries.

But underneath this veneer of modernity lies the real Pune, where the past continues to haunt the present. It’s a modern city that, to quote the scholar Meera Kosambi, remains proud of its “indigenous origins.”

The year 2014 perhaps marked Pune’s return to its original roots, even as the progressive movements and politics suffered a setback, both in its by lanes and New Delhi.

It can be said that through the decades, the city’s Congressmen and Socialists served both the city and the nation well.

It’s now up to the saffron parties to ensure the city retains its national standing and relevance.

The forthcoming parliamentary polls could be a good beginning. Pune deserves an MP who lives up to its formidable reputation, whichever party he belongs to.