Explained | Harnessing AI in healthcare

Mail This Article

The World Health Organisation (WHO) announced the launch of SARAH, a digital health promoter prototype with enhanced empathetic response powered by generative artificial intelligence (AI).

SARAH is a Smart AI Resource Assistant for Health.

It represents an evolution of AI-powered health information avatars, using new language models and cutting-edge technology.

It can engage users 24 hours a day in eight languages on multiple health topics, on any device.

The digital health promoter is trained to provide information across major health topics, including healthy habits and mental health, to help people optimise their health and well-being journey.

It aims to provide an additional tool for people to realise their rights to health, wherever they are.

SARAH gives us a glimpse of how artificial intelligence could be used in future to improve access to health information in a more interactive way

WHO calls for continued research on this new technology to explore potential benefits to public health and to better understand the challenges.

While AI has enormous potential to strengthen public health it also raises important ethical concerns, including equitable access, privacy, safety and accuracy, data protection, and bias.

Prioritising AI for health

• Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to the capability of algorithms integrated into systems and tools to learn from data so that they can perform automated tasks without explicit programming of every step by a human.

• Generative AI is a category of AI techniques in which algorithms are trained on data sets that can be used to generate new content, such as text, images or video.

• AI holds great promise for improving the delivery of healthcare and medicine worldwide, but only if ethics and human rights are put at the heart of its design, deployment, and use.

• Prioritising AI for health is crucial, given its potential to enhance healthcare and address global health challenges, including the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals.

• The urgency is exacerbated by a significant pacing gap, with technology outpacing legal frameworks.

• WHO is actively guiding Member States, developing ethical standards, and convening expert groups to address these challenges, promoting responsible AI development, and fostering collaboration among stakeholders to mitigate risks and safeguard public health and trust.

• WHO envisions a future where AI serves as a powerful force for innovation, equity, and ethical integrity in healthcare.

• To harness a culture of innovation and ethics in healthcare, WHO partnered with UN specialised agencies to establish the Global Initiative on Artificial Intelligence for Health, a collaborative effort that is shaping the future of healthcare through AI.

Harnessing artificial intelligence in healthcare

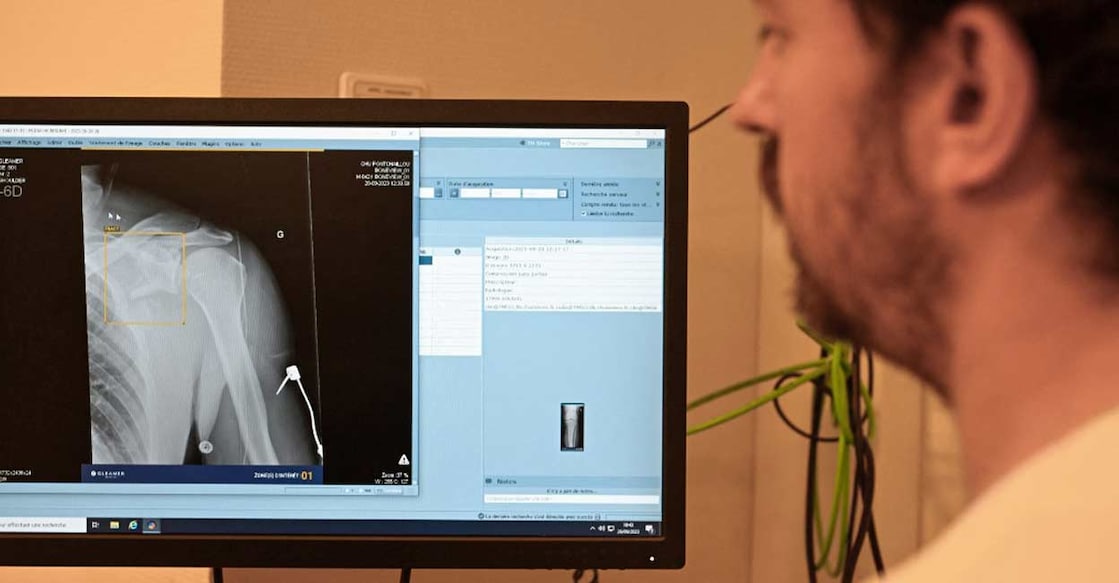

• AI is already used in diagnosis and clinical care, for instance to assist diagnosis in fields such as radiology and medical imaging, tuberculosis and oncology.

• It had been hoped that clinicians could use AI to integrate patient records during consultation, to identify at-risk patients and as an aid in difficult treatment decisions and to catch clinical errors.

• Applications of AI for health include drug development, healthcare administration and surveillance.

• AI-assisted X-rays could potentially detect health problems, such as tuberculosis, COVID-19, to further strengthen national diagnostic capacities.

• One type of generative AI, large multi-modal models (LMMs), can accept one or more types of data input and generate diverse outputs that are not limited to the type of data fed into the algorithm.

• LMMs are also known as “general-purpose foundation models”, although it is not yet proven whether LMMs can accomplish a wide range of tasks and purposes.

• LLMs include some of the most rapidly expanding platforms such as ChatGPT, Bard, Bert and many others that imitate understanding, processing, and producing human communication.

• It has been predicted that LMMs will have wide use and application in healthcare, scientific research, public health and drug development.

• LMMs are also known as “general-purpose foundation models”, although it is not yet proven whether LMMs can accomplish a wide range of tasks and purposes.

• LMMs usually have an interface and format that facilitate human-computer algorithm interactions that might mimic human communication and which can therefore lead users to imbue the algorithm with human-like qualities.

• Thus, the way in which LMMs are used and the content they generate and provide as responses, which may appear to be “human-like”, are different from those of other forms of AI and have contributed to the unprecedented public adoption of LMMs.

• Furthermore, because the responses they provide appear to be authoritative, many users uncritically accept them as correct, even if an LMM cannot guarantee a correct response and cannot integrate ethical norms or moral reasoning into the responses it generates.

• With rapid consumer adoption and uptake and in view of its potential to disrupt core social services and economic sectors, many large technology companies, startups and governments are investing in and competing to guide the development of generative AI.

• WHO recognises the tremendous benefits that AI could provide to health systems, including improving public health and achieving universal health coverage.

• However, it entails significant risks that could both undermine public health and imperil individual dignity, privacy and human rights.

• Even though LMMs are relatively new, the speed of their uptake and diffusion led WHO to provide this guidance to ensure that they could potentially be used successfully and sustainably worldwide.

1) Use of LMMs in diagnosis and clinical care

• LMMs could make it possible to extend use of AI-based systems throughout diagnosis and clinical care – both virtual and in-person consultations, with some experts expecting that LMMs “will be more important to doctors than the stethoscope in the past”.

• Diagnosis is seen as a particularly promising area, because LMMs could be used to identify rare diagnoses or “unusual presentations” in complex cases.

• Doctors are already using Internet search engines, online resources and differential diagnosis generators, and LMMs would be an additional instrument for diagnosis.

• LMMs could also be used in routine diagnosis, to provide doctors with an additional opinion to ensure that obvious diagnoses are not ignored.

• All this can be done quickly, partly because an LMM can scan a patient’s full medical record much more quickly than can doctors.

Risks of use of LMMs in diagnosis and clinical care:

i) Inaccurate, incomplete, biased or false responses: False responses, known colloquially as “hallucinations”, are indistinguishable from factually accurate responses generated by an LMM, because even LMMs with reinforcement learning from human feedback are not trained to produce facts but to produce information that looks like facts.

ii) Data quality and data bias: One reason that LMMs produce biased or inaccurate responses is poor data quality. Most medical and health data are also biased, whether by race, ethnicity, ancestry, sex, gender identity or age.

iii) Automation bias: Concern that LMMs generate false, inaccurate or biased responses is heightened by the fact that, as with other forms of AI, LMMs are likely to encourage automation bias in experts and healthcare professionals. In automation bias, a clinician may overlook errors that should have been spotted by a human.

iv) Skills degradation: There is a long-term risk that increased use of AI in medical practice will degrade or erode clinicians’ competence as medical professionals, as they increasingly transfer routine responsibilities and duties to computers. Loss of skills could result in physicians being unable to overrule or challenge an algorithm’s decision confidently or that, in the event of a network failure or security breach, a physician would be unable to complete certain medical tasks and procedures.

v) Informed consent: Increased use of LMMs, in person but especially virtually, should require that patients are made aware that an AI technology may be either assisting in a response or could eventually be responsible for generating a response that will mimic a clinician’s feedback. Yet, if and when LMMs and other forms of AI are merged into regular medical practice, patients or their caregivers, even if they are uncomfortable or unwilling to rely wholly or partially on an AI technology, may be unable to withhold consent for its use.

2) Use of LMMs in patient-centred applications

• People are using the Internet to obtain medical information. AI is beginning to change how patients manage their own medical conditions.

• Patients already take significant responsibility for their own care, including taking medicines, improving their nutrition and diet, engaging in physical activity, caring for wounds or delivering injections.

• AI tools have been projected to increase self-care, including by the use of chatbots, health monitoring and risk prediction tools and systems designed for people with disabilities

• LMM-powered chatbots, with increasingly diverse forms of data, could serve as highly personalised, broadly focused virtual health assistants.

Risks in patient-centred applications

i) Inaccurate, incomplete or false statements: Use of LMMs by patients is associated with risks of false, biased, incomplete or inaccurate statements, including from AI programmes that claim to provide medical information. The risks are heightened when used by a person without medical expertise, who will have no basis for challenging the response, have no access to another source of information or when used by children.

ii) Manipulation: Many LMM-powered chatbot applications have distinct approaches to chatbot dialogue, which is expected to become both more persuasive and more addictive. Chatbots can provide responses to questions or engage in conversation to persuade individuals to undertake actions that go against their self-interest or well-being.

iii) Privacy: Use of LMMs by patients may not be private and may not respect the confidentiality of personal and health information that they share. Users of LMMs for other purposes have tended to share sensitive information, such as company proprietary information. Data that are shared on an LMM do not necessarily disappear, as companies may use them to improve their AI models, even though there may be no legal basis for doing so. Thus, if a person’s identifiable medical information is fed into an LMM, it could be disclosed to third parties.

iv) Degradation of interactions between clinicians and patients: Use of LMMs by patients or their caregivers could change the physician-patient relationship fundamentally. The increase in Internet searches by patients has already changed these relationships, as patients can use the information they find to challenge or seek more information from their healthcare provider. While an LMM could improve such dialogue, a patient or caregiver might decide to rely wholly on an LMM for prognosis and treatment and thereby reduce or eliminate appropriate reliance on professional medical judgement and support. A related concern is that, if an AI technology reduces contact between a provider and a patient, it could reduce the opportunities for clinicians to promote health.

v) Epistemic injustice: Epistemic injustice is a “wrong done to someone specifically in their capacity as a subject of knowledge”, such as a patient in a healthcare system. One form of epistemic injustice, hermeneutic injustice, occurs when there is a gap in shared understanding and knowledge that puts some people at a disadvantage with respect to their lived experience, social experience or, in the case of healthcare, their own understanding of their physical or mental condition. If a patient’s experience is not acknowledged or recognised in a clinical setting by an LMM, it can obviate appropriate care from a medical provider, which could harm the patient. This is especially likely for vulnerable groups that are already neglected and under-represented in data.