What’s going on in your life right now? Are you IMing your friends, responding to emails, browsing the web, working on tomorrow’s client presentation, and doing all this while listening to music and leaving the TV on in the background?

Who can remember life before multi-tasking? From circa 1965 when this avant-garde name was first used to describe the capabilities of the IBM System / 360, it now has the virulence of the common cold, infecting mothers, air-traffic controllers, hospital doctors, high-flying executives, and apparently the entire brigade of millennials, brazenly flaunting their “digital natives” tag.

But even as juggling multiple tasks seems to have become the norm, in recent years a chorus of voices has begun questioning the premise that multi-tasking is the answer to managing heavy workloads and a fast-paced environment.

Perhaps the problem begins with what we mean by “multi-tasking” in the first place. Different people seem to mean different things: Some use the term to refer to those who juggle multiple roles in their daily lives – e.g., as fitness guru, media personality, mother and wife. Others use it to mean performing two or more tasks simultaneously: for instance, ironing clothes while listening to a podcast.

But what exactly is happening when you claim you’re spending quality time with family while you research stocks online, share an Instagram story on Facebook, do an occasional check on breaking news – and pretend to listen to your spouse narrate her day at the office? Are you really doing all this simultaneously? Hardly. What’s actually happening is that you’re switching back and forth among all these various tasks, crunching a few numbers here, tossing your spouse a “hmm” there, digesting a TV news grab the next minute. It might be more appropriate, say the productivity experts, to call this sort of thing “switch-tasking” rather than “multi-tasking.” Because what’s going on is actually a process of switching attention rapidly among a number of different activities.

So, we may be talking apples and oranges here. And research shows that doing two tasks simultaneously – true multi-tasking – is possible only when one of the tasks is a routine, low-level, non-demanding task or activity that you can do on auto-pilot – say, walking with a friend and talking. But if both the tasks require a cognitive input, such as focusing, it’s impossible to do them simultaneously.

Up the down staircase

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesThe findings from scientific studies lead us to certain inevitable – and not-so-happy -- conclusions about multi-tasking:

It’s not an efficiency boost, it’s a brain drain. Though the human brain can process multiple kinds of information, we can only pay attention to one thing at a time. We do have peripheral awareness of other things going on, i.e., information on the periphery of our awareness can grab our attention. We may turn our attention to that peripheral input and then come back to the task on hand. But a number of independent lines of research all lead to the same conclusion – we can’t actually pay attention to multiple things at the same time. We must complete the first task, or part of that task, before shifting focus and doing another. One way this has been described is as “continuous partial attention.”

Think you’re saving time? Think again. Switching between tasks also exacts its price in the amount of time we spend on these tasks. That’s what the research spilling out of labs is telling us. For instance, in one typical experiment, subjects were asked either to check their e-mail and then write a report — the two tasks performed sequentially — or to do both tasks at the same time. The multi-taskers took one and a half times as long as those who did one task and then another.

This finding has been confirmed by numerous other studies. They all show that there is a “switching cost” every time you change from one task to another -- simply because of the time required for the brain to change gears. And the more complex or unfamiliar the tasks, the longer the time taken to switch between them. In some cases, these studies show, you need as much as four minutes to get back to maximum productivity on a task after an interruption. Now, if you’re trying to juggle four tasks, you could lose as much as sixteen minutes in one cycle of task-switching alone.

Why does this happen? Studies by neuroscientists indicate that each time a person switches back and forth between tasks, the brain goes through several time-consuming activities, including:

» a selection process for choosing a new activity

» turning off the mental rules needed to do the first task

» turning on the mental rules needed to do the second task

» orienting itself to the conditions currently surrounding the new task

Think you’re good at multi-tasking? Think again. Researchers at Stanford who gave multi-taskers and uni-taskers three standard tests of attention, found that multi-taskers uniformly fared worse on all three tests, compared to uni-taskers. What was equally – if not more – interesting was that all the multi-taskers had believed they were good at multi-tasking.

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesBut why are high multi-taskers worse at standard tests of attention? This needs further exploration. Perhaps multi-tasking dulls our mental abilities – we lose the ability to focus, to filter out extraneous information, and to quickly shift our attention to a necessary task. Or, perhaps high multi-taskers fare poorly because they naturally have poor attention skills in the first place, or don’t recognize the negative impact multi-tasking has on their performance. Maybe low multi-taskers are better able to detect the deleterious effects that multi-tasking has on attention and performance.

It vitiates the creative process of flow. Multi-tasking has also been found to run interference with what has been called a “state of flow” – the kind of experience in which, say, a musician loses herself in her music, or a painter becomes one with the process of painting. It’s a mental state in which, not just a musician or a painter, but even a driver gets completely caught up in his or her work. Flow is a singularly productive and desirable state, but flow follows focus. It is a state that can show up only when all your attention is focused in the right here, right now. It’s obvious that the interruptions – however small – that trail in with switch-tasking can put flow to flight.

To illustrate with an extreme example: Imagine if Einstein had hop-scotched between poking at a Smartphone, reading a Kindle, writing a scientific paper, and playing a challenging online strategy game at the same time that he was working on General Relativity. We’d probably still be living in the age of Newton. In fact, Einstein himself had quite definite notions about multi-tasking, and once jestingly said, “Any man who can drive safely while kissing a pretty girl is simply not giving the kiss the attention it deserves.”

It lowers your work quality and efficiency. Multi-tasking makes it more difficult to organize thoughts and filter out irrelevant information, and it reduces the efficiency and quality of your work.

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesIt has also been found to increase production of cortisol, the stress hormone. Having our brain constantly shift gears pumps up stress and tires us out, leaving us feeling mentally exhausted (even when the work day has barely begun).

Some of the other fallout of multi-tasking may be more serious. A University of London study found that people distracted by constant incoming e-mail and phone calls saw a 10- to 15-point fall in their IQs, essentially turning them into the mental equivalents of 8-year-olds. (For some reason, the steeper falls in IQ are seen in men). How does such a significant drop in IQ translate in terms of its impact on work? The research scientists said it’s the same as losing a night of sleep and more than twice the effect of smoking marijuana.

The news gets worse. The most recent research suggests that the cognitive damage linked to multi-tasking could be permanent. Typical is the finding from the University of Sussex where researchers ran MRI scans on the brains of men who habitually used multiple devices at the same time (e.g., texting while watching TV). The research found that high multi-taskers had less grey matter in those brain regions responsible for emotional and cognitive control.

It can be a medical hazard and sometimes life-threatening. In some professional spheres like medicine, multi-tasking can carry critical risks in human terms. We have a ton of research indicating that multi-tasking is ubiquitous in healthcare settings and poses a risk to patient safety. Two typical studies, one from Australia and another from the U.S., looked at the cost of multi-tasking resulting from frequent interruptions in the work of Emergency Room (ER) physicians. These doctors operate in a dynamic environment that has been identified to be at greater risk of errors than many other settings. The Australian study found that, faced with frequent interruptions, ER doctors left 1 in 5 ER tasks incomplete; multi-tasking several times an hour was also found to jeopardize the physicians’ ability to care for patients by increasing the potential for error. A common scenario was that of a physician trying to complete a simple but necessary task, such as writing a prescription, only to be interrupted by a crisis in the emergency room. “At the very moment when you’re deciding what medicine to give them and what dose, you have a gunshot to the chest coming in the door, and you may either not finish the order or may not carefully dose the medication,” one physician in the study said.

At the St. John Hospital and Medical Center in the U.S., the majority of interruptions were found to be related to constant requests for electrocardiogram (ECG) interpretation. Because 95% of the ECGs are not indicative of heart attack, one doctor noted, “It's easy to get into a habit of saying, ‘Oh, sure, it’s fine,’ without carefully looking at the test.”

When mistakes are made, patient harm is often averted, the studies found, as a result of questions raised by nurses or through inconsistencies in electronic records.

5 ways to save your brain

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesThe most effective solutions are often the simplest. Here they are:

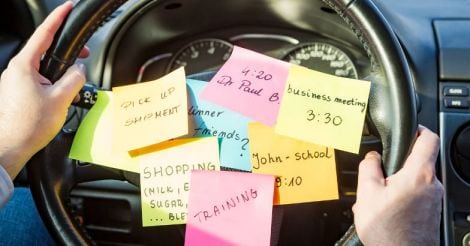

1. Put it down; prioritize. The sheer number of tasks on your plate each day can seem overwhelming, and in desperation or despair you try to do several of them all at once. To-do lists are greatly under-valued, but they are a good starting point. If, instead of trying to keep all of those things-to-do in your head, you put them down in a list, you let go of the need to remember to a large extent.

But keep that list realistic. If it’s unreasonably lengthy, you risk feeling bad (read guilty!) when all those things don’t get done, you even risk forgetting about the tasks you did manage to successfully complete.

This underlines the importance of prioritizing. Put down first the most urgent and important tasks for the day. Block out the time for these tasks, then pencil in the others. Some of the less important tasks may stay undone, and they can be carried forward to the next day.

When you don’t prioritize, you can find yourself starting off the day with pleasurable things like calling a friend to gab about the great party you went to last night, while high-payoff tasks like following up on referrals, returning calls to current clients, generating leads, get sidelined. Everyone knows what their high-priority tasks are, but you need to focus on them and make them happen.

2. Group together similar tasks. To save time, try a different approach from multi-tasking: grouping related tasks together. If you have to write out five cheques, write them one after the other. If you have several outdoor chores, see whether you can cover all or most of them in one trip. Try to find some sort of narrative to club tasks together. That’ll reduce the time and effort you need to put into them – and actually bring you the benefits that you imagine multi-tasking is bringing you today.

3. Establish an email checking schedule. Despite the popularity of instant messaging, texting and social media, surveys show that email is the top communication tool at work and is slated to grow in importance over the next five years. The constant thrill of a new, bold-fonted email in the Inbox can keep many people in a state of eternal distraction. Research finds that some addicts of the Inbox can spend the greater part of their working day checking emails for both, work-related and personal messages. In addition, 1 in 4 admit to checking email while driving.

Commit yourself to checking emails only three times a day—say, when you get to work in the morning, at lunch time and before leaving work at the end of the day.

One workplace that tried this approach to email detox found it highly effective. Employees at this company who fudged on the policy and checked e-mail throughout the day were not as productive as the others -- and couldn’t seem to figure out how other staff got so much more done.

4. Ditto for texting. Problematic as email is, texting is worse, demanding even more immediacy than email, having us check it more adamantly as a result. Turn off texting notifications and choose specific times to check your phone as well. And inform clients, friends and others in your network about this upfront so they know what to expect. For urgent matters, there’s still the phone call.

5. Deal with distractions. As a dedicated multi-tasker on the path to reform, you’ll find, from time to time, that you’re being niggled by a desire to interrupt yourself by checking your e-mail, getting on to Facebook, or whatever. If you notice those temptations arising, okay notice them and then let go of them. They’ll pass.

So there they are -- strategies for halting the multi-tasking massacre. Spend some time exploring their possibilities — but not too much time. Isn’t there something else you should be doing?

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty Images